The Petition Again

(1937–1938)

Approaching the federal government

After Arthur Burdeu began to play a role in the League’s affairs, the importance of Cooper’s petition to the King receded for a while. Cooper soon insisted that it be taken up again, but it seems that both Burdeu and Rev. William Morley, the secretary of the Association for the Protection of Native Races, persuaded him to set it aside. Burdeu was apprehensive that the Commonwealth government might refuse to allow it to reach the Governor-General, let alone the King, while Morley believed that the federal government would refuse to accept the petition on the grounds that Aboriginal affairs was largely the province of the states rather than the Commonwealth. Eventually Cooper agreed to postpone the submission of the petition until the League learned the outcome of the first ever meeting of the administrators of Aboriginal affairs, which took place in April 1937.

Submitting the petition

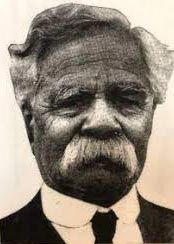

Cooper was bitterly disappointed by the outcome of the meeting of the administrators of Aboriginal affairs, telling Thomas Paterson, the Minister for the Interior: ‘We asked [for] bread. We scarcely seem likely to get a stone’. He warned Paterson that unless the government acted, he would submit his petition to the King. But he soon lost patience and word got around that he had decided that enough was enough and that he would send off the petition. Learning of this, a leading journalist, Clive Turnbull, interviewed Cooper and his newspaper, the Melbourne Herald, published a long article that included a photo of Cooper. Cooper showed Turnbull the rolls of signatures and told him: “Some tell us that the King has no power now in these things, but we shall try anyway.”

The reaction of newspapers to the petition

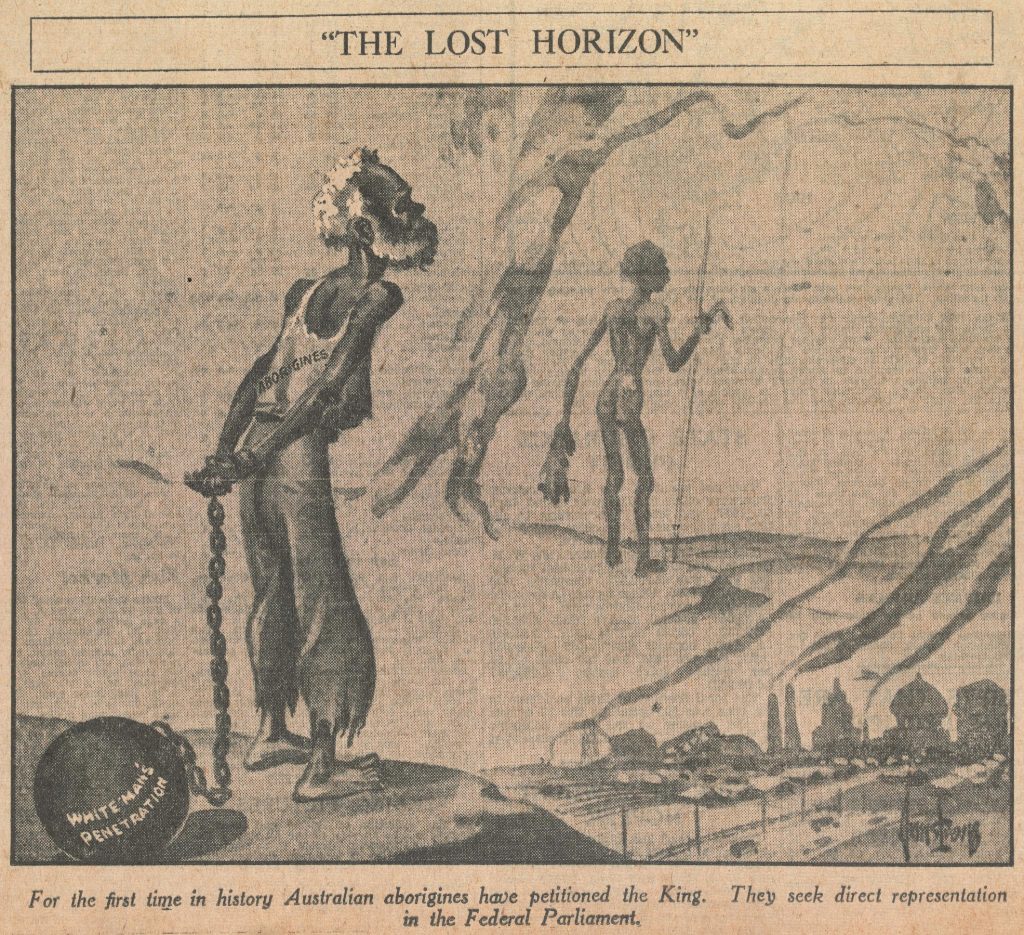

Several weeks after Cooper submitted the petition to the Governor-General, Lord Gowrie, the League tried to put pressure on the government by informing the press that Prime Minister Joseph Lyons had promised to give it early consideration. A large number of newspapers around the country and a few overseas carried reports about it. Many of them were sympathetic to its call for protection and parliamentary representation, especially the labour and left-wing newspapers. More than one newspaper devoted editorials or commentaries to it and at least two published cartoons about it. But other newspapers were scathing.

The government’s response

Lyons seems to have been willing to countenance the demands Cooper made in his petition. At any rate, the federal government’s senior legal officer was asked for advice. But the secretary of the Department of the Interior, J. A. Carrodus, was dismissive of the petition’s key demand. He persuaded his minister there was nothing to be gained from forwarding the petition to the King and cabinet accepted this view. But Cooper was never informed of this decision. As a result, he continued to press the cause of his petition. In the first instance, in March 1938, he prepared what might be regarded as his political testament, ‘From an Educated Black’, in order to explain the nature of the demands he and the League had been taking. And in August 1940, in the last letter he ever wrote as the League’s secretary, he begged Prime Minister Robert Menzies to attend to the petition’s principal demand.