The Cumeroogunga Walk-off

(1939)

Many of the matters that Cooper took up in his political campaign had a national dimension, but local matters were also important for both him and his Aboriginal associates. In this respect, Cumeroogunga was to the fore. This is hardly surprising given that it was home for most of the members of the League.

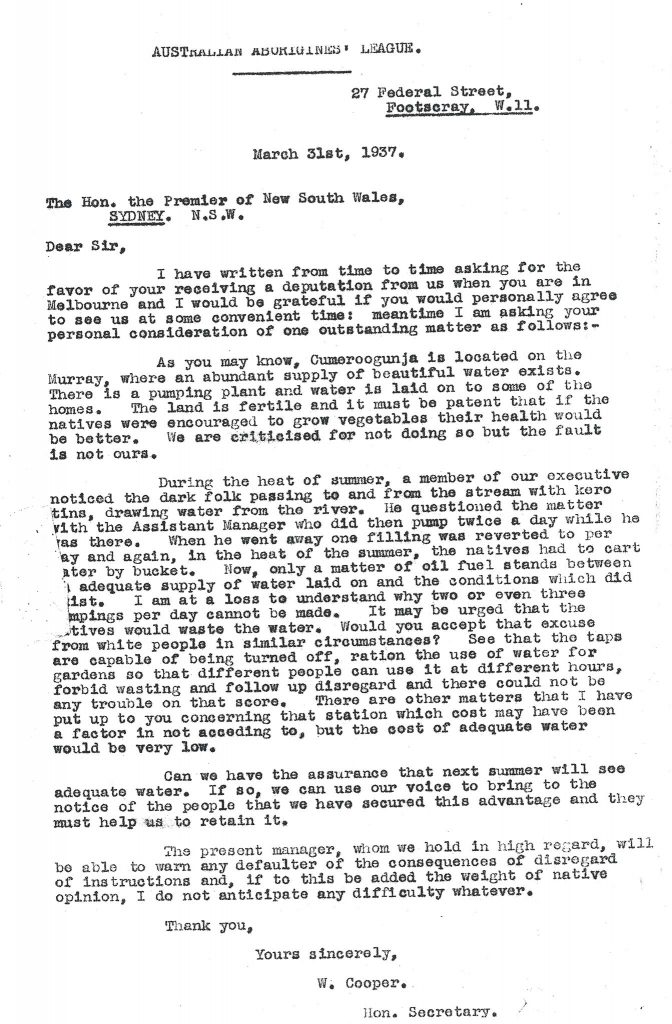

In 1936, after the League had been re-formed, Cooper began a campaign to persuade the New South Wales government to develop Aboriginal reserves in the state. He urged to use Cumeroogunga as an example of what could be done.

Protest

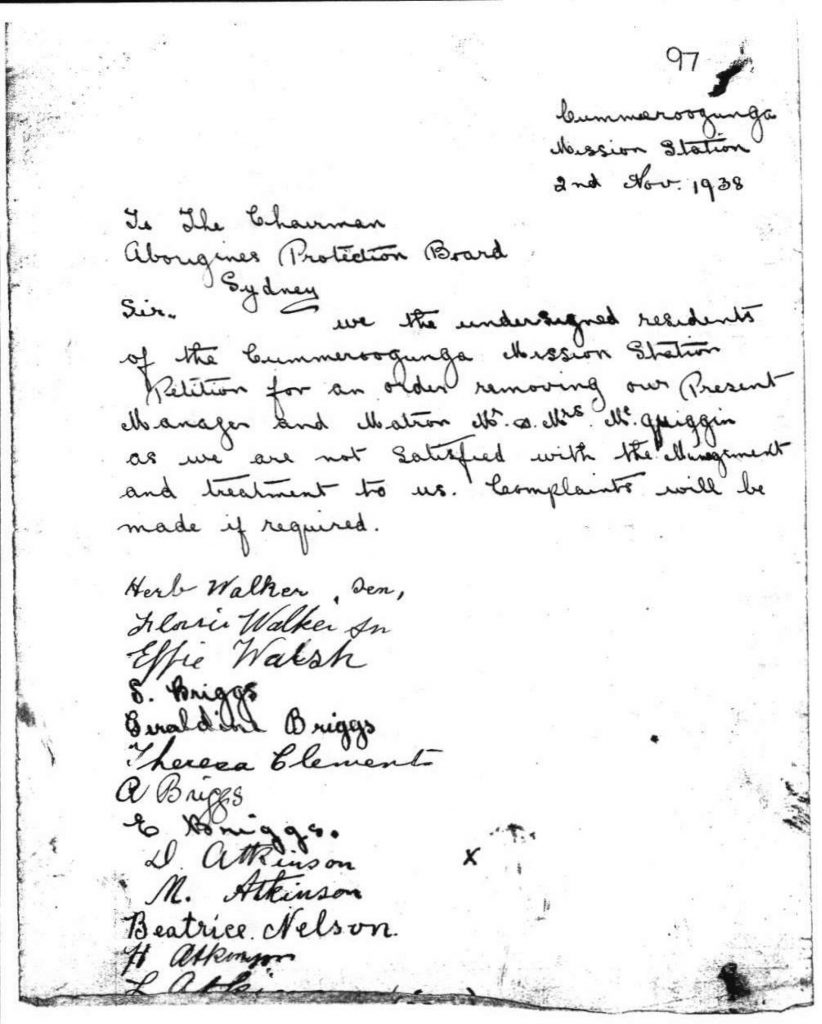

Conditions on Aboriginal reserves in New South Wales deteriorated in the course of the 1930s and on Cumeroogunga relations between the people and the Aborigines Protection Board took a turn for the worse in mid 1937 after the Board had transferred a well-liked manager to another reserve and appointed a notoriously authoritarian figure, Arthur McQuiggan, in his place. Conflict broke out on the reserve soon after McQuiggan took over and came to a head when many of the people signed a petition calling for his removal.

Walk-off

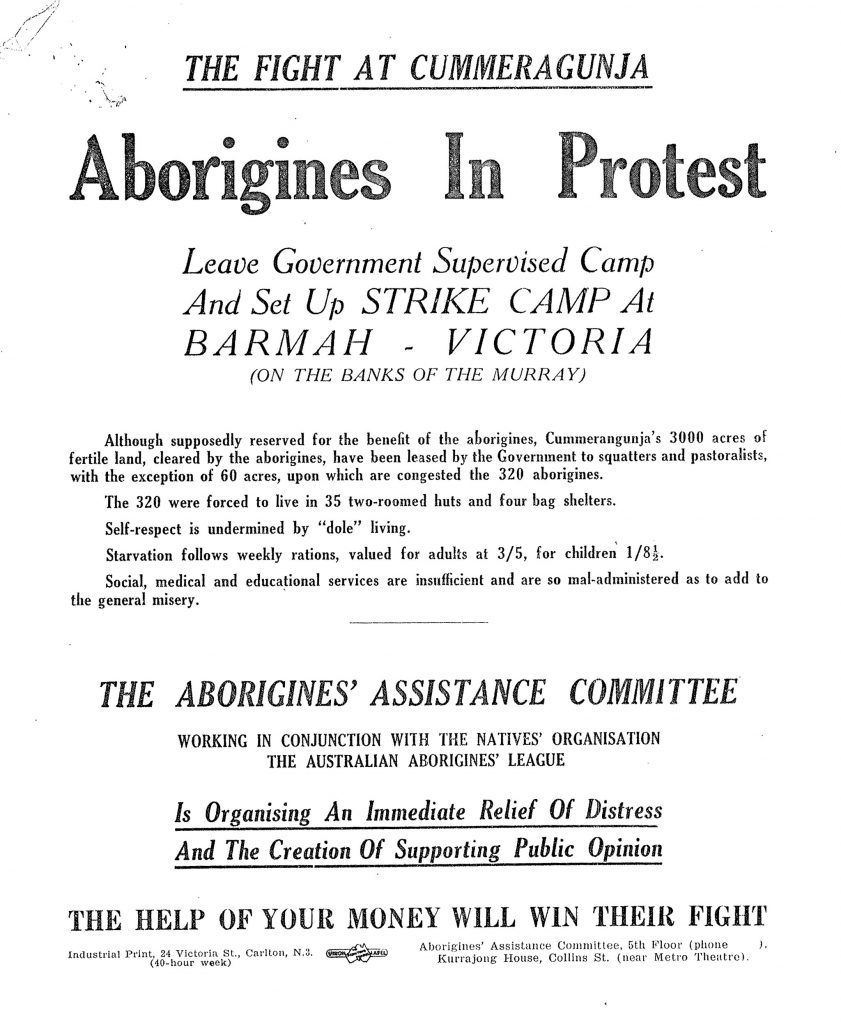

In late January 1939 Jack Patten, the President of the Aborigines Progressive Association, addressed a meeting at Cumeroogunga and urged the people to walk off the reserve. Shortly afterwards, many began to do so and Patten and Cooper sent a telegram to the New South Wales government and the press demanding an immediate inquiry. Yet both Cooper and Burdeu were ambivalent about the protest. The League had long had a preference for forms of political action that comprised representations of one kind or another, whether this involved addressing appeals to government, penning letters to the editors of newspapers, making statements to the press, holding public meetings or staging concerts. They were apprehensive that the walk off would alienate the League’s white supporters. However, in the course of the next few months the League assumed responsibility for explaining the causes of the walk-off to the press, fighting for a government inquiry and providing material support for the protestors who made a camp at Barmah.

Aborigines Assistance League

At the time of this protest, Cooper’s health began to fail and Burdeu fell ill. As a result, younger members of the League, most importantly Doug Nicholls and Margaret Tucker, started to play a greater role in its affairs. Furthermore, left-wing forces joined with the League to form a new organisation, the Aborigines Assistance Committee, to support the walk-off (or the strike as the left-wing press styled the protest). George Patten became the Committee’s organiser.