Remembrance

(2000-2020)

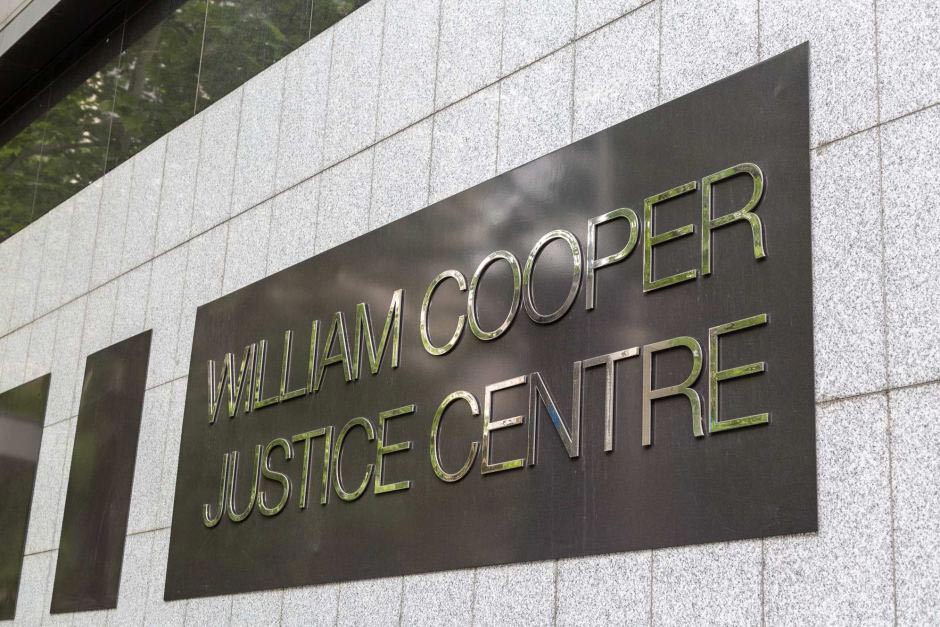

In the last fifteen years William Cooper has become better known in Australia as he has been honoured in various forms that have included painting, sculpture and opera. In many of these acts of remembrance — such as the naming of a railway bridge in Footscray — he has been hailed for the main thrust of the political work that he undertook on behalf of his people, most notably his petition to the King.

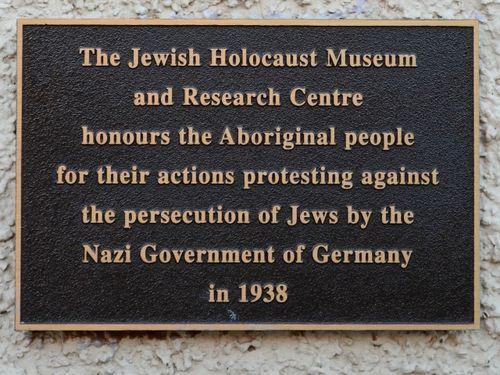

However, most of commemorative activity in recent years has focused on the fleeting protest against Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jewish people that the Australian Aborigines’ League made when it delivered a petition to the German Consulate in Melbourne in December 1938. This is the case even though most academic historians regard this act as relatively insignificant.

A particular way of telling the story of this protest — which the great European historian Eric Hobsbawm would have regarded as an example of the invention of tradition — has come to dominate how Cooper is known among non-Indigenous people today. In this version he bears witness to an event — the Jewish Holocaust — that had yet to happen.

This story has narrowed understanding of Cooper and the Australian Aborigines’ League, obscured the forces that enabled their campaigning, making it difficult to grasp what their political work entailed and why it is worth remembering.