The League

(1933–1936)

The forming of the League

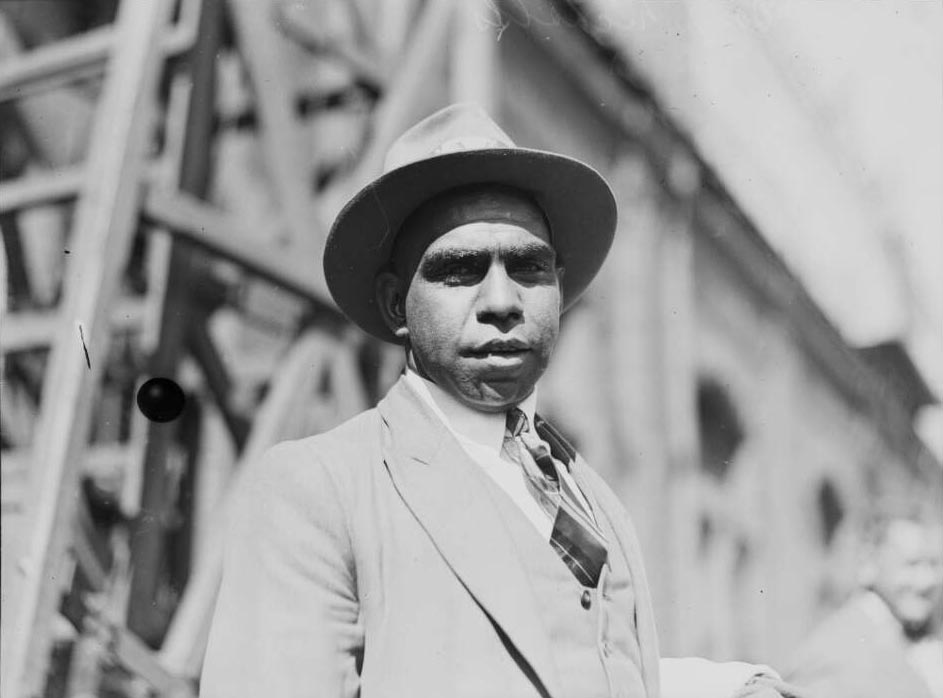

William Cooper’s name is inextricably bound up with the Australian Aborigines’ League. This organisation is often confused with another organisation with the same initials — the Aborigines Advancement League — that was formed in Melbourne many years later. But while they had some figures in common and some of the same concerns, they were distinct organisations.

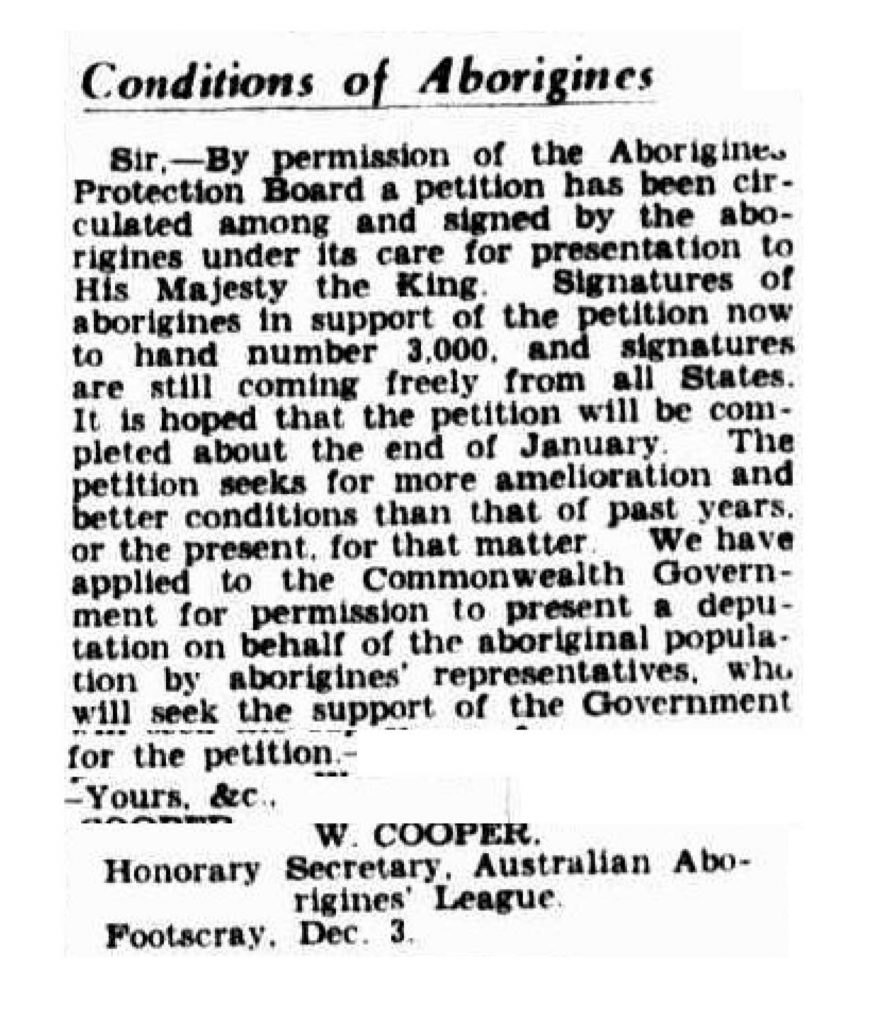

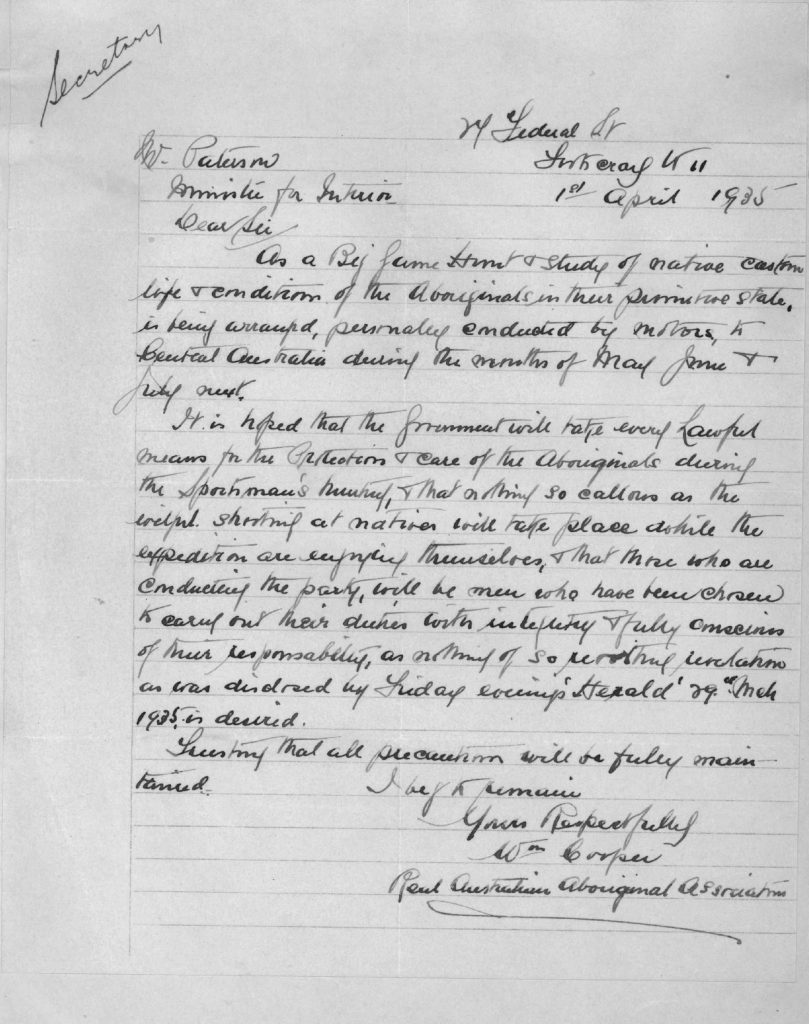

Several historians have argued that the Australian Aborigines’ League was only founded in 1935 or 1936 after a white man (Arthur Burdeu) became involved in Cooper’s work. However, this overlooks the fact that Cooper had formed an organisation earlier, in 1933, though it was not until December 1934 that he sent material out in this name, and several months later he sent a letter to the federal government on behalf of the ‘Real Australian Aboriginal Association’.

The reformation of the League

By the middle of 1935 Cooper was feeling the burden of leading the League’s campaign. Indeed, his work had practically ground to a halt. Part of the problem lay in the fact that he lacked the financial means to sustain it. He appealed to the federal government for help, but was rebuffed. At this point A.P.A. (Arthur) Burdeu came to his rescue. More than twenty years younger than Cooper, this whitefella was a trade unionist with leftist sympathies, but above all else he was a fervent Christian. Both factors enabled Cooper and Burdeu to see eye to eye on many matters and work together relatively harmoniously. But the most important factor in the two men being able to combine forces as well as they did lay in the fact that Burdeu respected Cooper’s wish that the organisation remain an Aboriginal one. As Burdeu declared once, in the context of explaining differences between Cooper’s organisation and white organisations campaigning on behalf of the Aboriginal people, ‘The League is the Aboriginal Voice’.

The League’s constitution

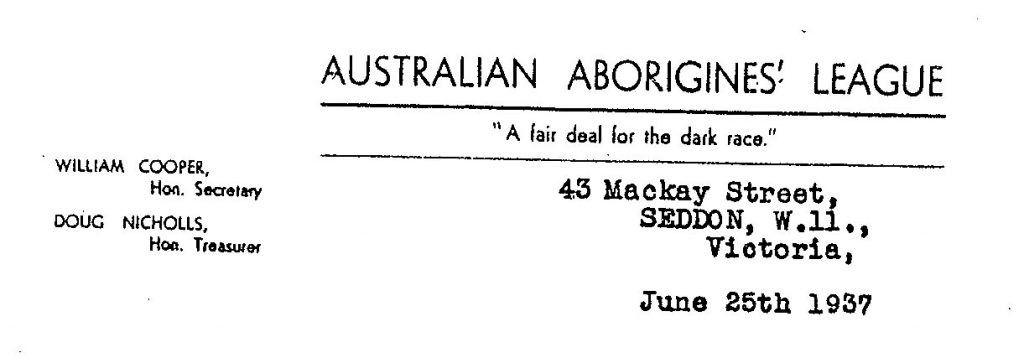

After Burdeu became involved, the League was formally constituted as an organisation. By February 1936, if not a few months earlier, it had acquired a constitution [This should have a hyperlink to a document in the Archive], a programme and office bearers, though the formation — or what really amounted to its reformation — was announced a few months earlier in an article to the labour press. Cooper became the League’s secretary and Doug Nicholls its treasurer; Lynch Cooper was appointed its assistant secretary, Margaret Tucker, Mary Clarke and Doug Nicholls became its vice-presidents, and its executive committee comprised these people as well as Annie Lovett, Hyllus Briggs, Marie Lovett, Julia Niven, Alice Clarke and Caleb Morgan.

The League, style and strategy

Burdeu’s involvement resulted in a considerable expansion of the League’s activities. It made many more approaches to government but also overtures to other like-minded white organisations. As Burdeu became primarily responsible for the League’s strategy, the organisation became a more effective champion of Cooper’s cause. Its appeals to government also acquired more focus: problems were specified, supporting arguments provided, particular solutions recommended. The League also acquired a slogan — ‘A fair deal for the dark race’ — which Burdeu seems to have suggested, and a letterhead — which he probably designed.