Maloga Mission

(1874–1887)

Founding

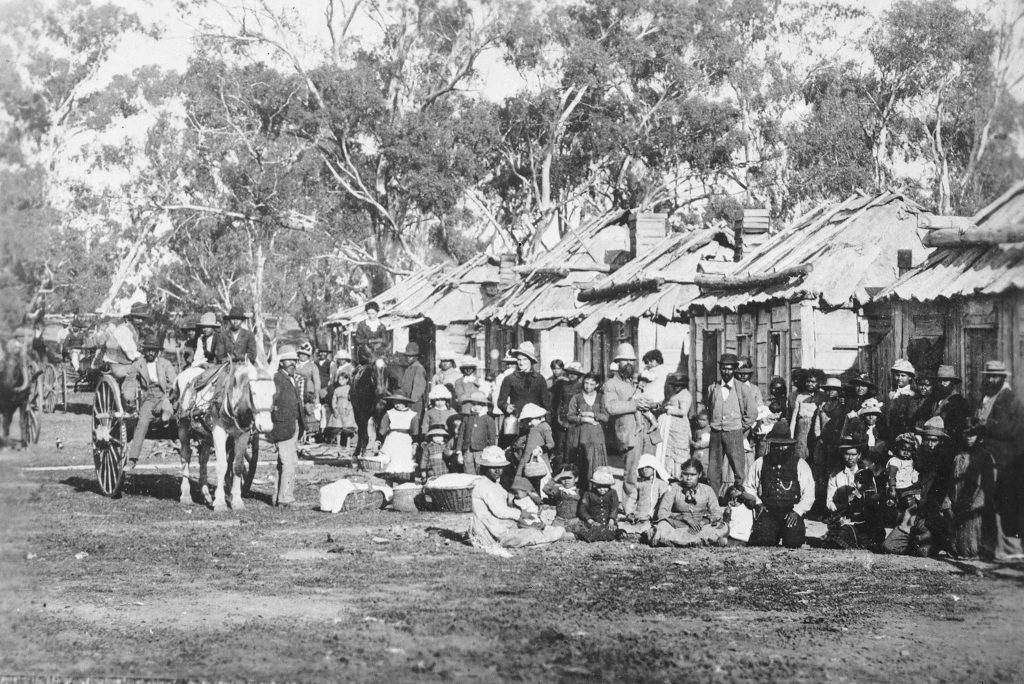

William Cooper’s life course was profoundly influenced by his encounter with Christian missionaries Daniel and Janet Matthews in August 1874, shortly after they founded a mission to cater for the needs of Aboriginal children. Missions to Aboriginal people in the southeastern Australian colonies had become quite common by this time, but Maloga was unusual: it was neither sponsored nor supported by a church or a missionary society and it lay on private land. It was more typical in that the local Aboriginal people played a role in choosing the site and perhaps its name. Located on the Barmah sandhills at a beautiful bend of the Murray River, Maloga was favoured by the Yorta Yorta because it was one of their traditional ceremonial grounds.

Cooper was one of Daniel Matthews’ first acolytes at Maloga, impressing him by his aptitude to learn reading and writing. In the eyes of Christian missionaries, the attainment of skills such as reading and writing, as well as building houses and farming the land, were evidence that Aboriginal people could be ‘civilised’. Cooper encouraged his mother and younger siblings to accept the mission’s protection from exploitation by settlers, but he himself did not stay as its future was precarious and it could offer him little work, let alone wages. Yet his support for the mission probably caused a breach in his relationship with the local pastoralists and as a result it seems he had to look elsewhere for work. This took up as far away as Central Australia and even New Zealand.

Conversion

Mortlock Library

In the summer of 1883-84 Cooper was one of many at Maloga to convert to Christianity. A religious revival at the mission gathered momentum after Matthews and the Aboriginal people moved to the Moira Lakes to camp for a week or two. On their customary ground there, several Yorta Yorta men, including Cooper’s brothers Aaron and Johnny Atkinson, played a key role in converting their kin. Their embrace of Christianity probably owned something to a perception that it could bring material advantages. Several months earlier, the New South Wales government had granted an adjacent block of land in response to a petition by the Maloga men, and Matthews and his religious backers had played a role in facilitating this outcome.

Singing

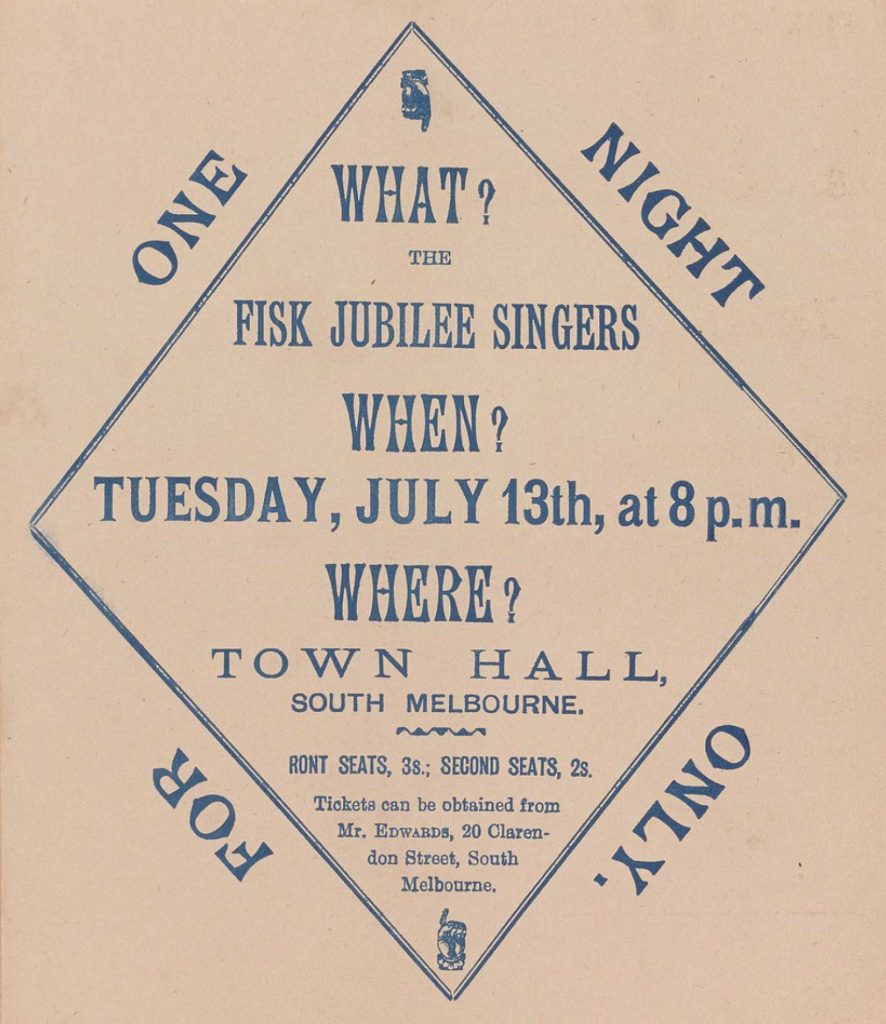

From Maloga’s beginnings the Matthews taught their acolytes hymns. Singing them became an important party of the mission’s spiritual life. This acquired a new dimension when the celebrated African American group, the Fisk Jubilee Singers, visited the mission in 1886. The pain and suffering expressed by the slave songs they sang evidently struck a chord. ‘Many of them wept as they listened to the weird plaintive melodies’, its director wrote. As the Jubilee Singers left, the Maloga choir sang ‘Blest be the tie that binds’ and the visitors reciprocated by singing ‘Good-bye brothers, good-bye sisters’.

Afterwards, the Maloga people mastered several of the Jubilee Singers’ spirituals, including one translated into Yorta Yorta, ‘Burra Phara’, which envisions the return of the dispossessed to their homeland.

Advertisement, 1887, Beinecke Library,

Yale University

Ngarra Bura Phara

Womriga Moses yinin walla

Walla yupna yeipuch

Nara Bura Fera yumena yalla

[Chorus]

Nara Bura Fera

Yumena yalla yalla

Nara Bura Fera

Yumena yalla yalla

Nara Bura Fera Yumena

Bura Fera Yumena

Bura Fera Yumena

Yalla yalla

Nyundo peco Jesu

Bora bocono yumena

Nara Bura Fera

Yumena yalla

[Chorus]

English translation of the second verse:

We’re going to pray to Jesus

To bring some valiant soldiers

To drown old Pharaoh’s army

Alleluia

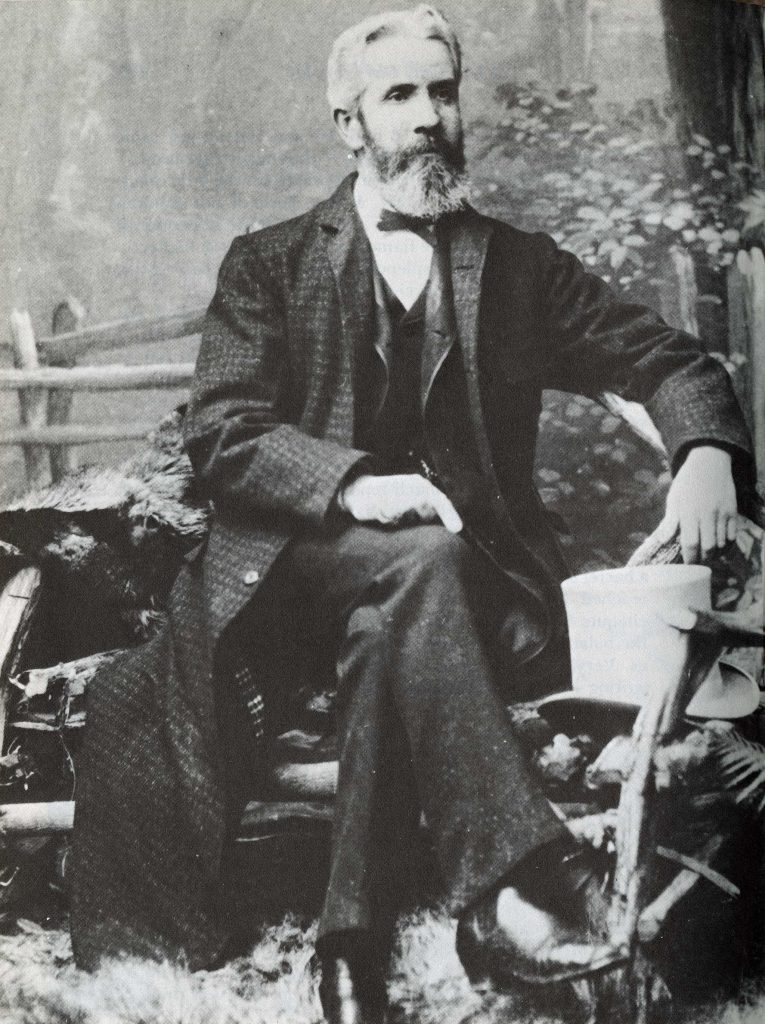

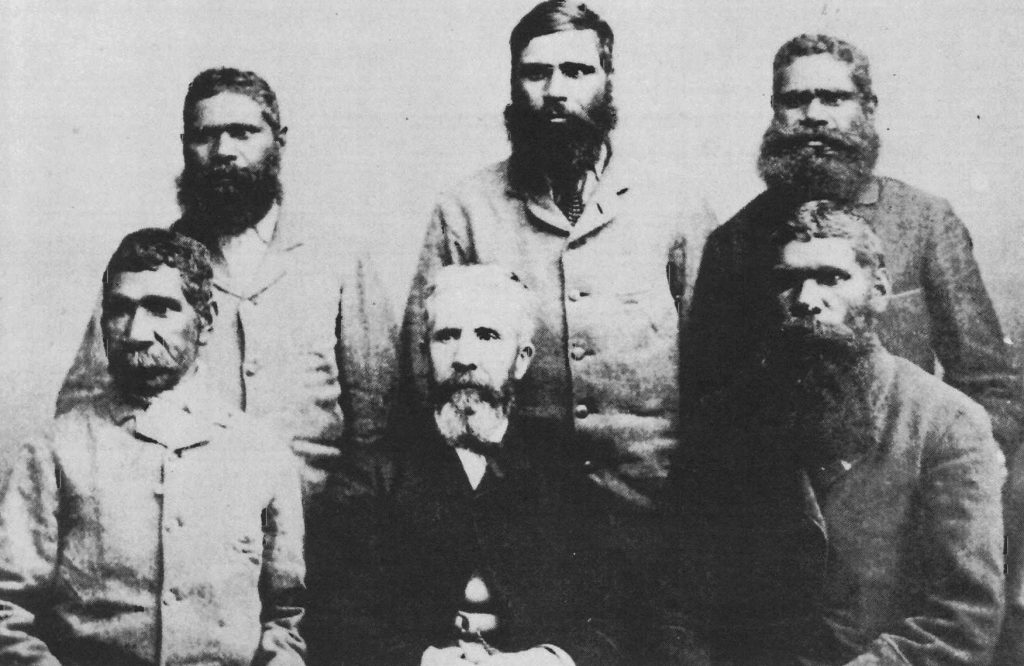

Thomas Shadrach James

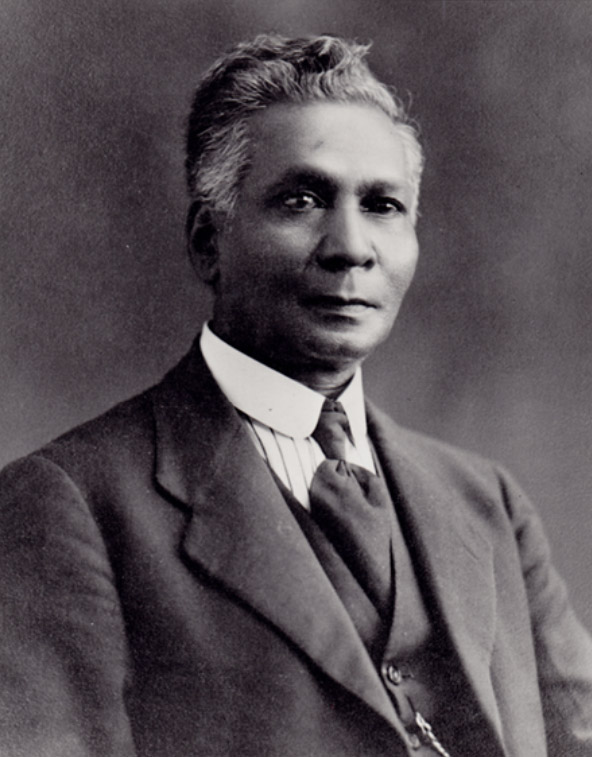

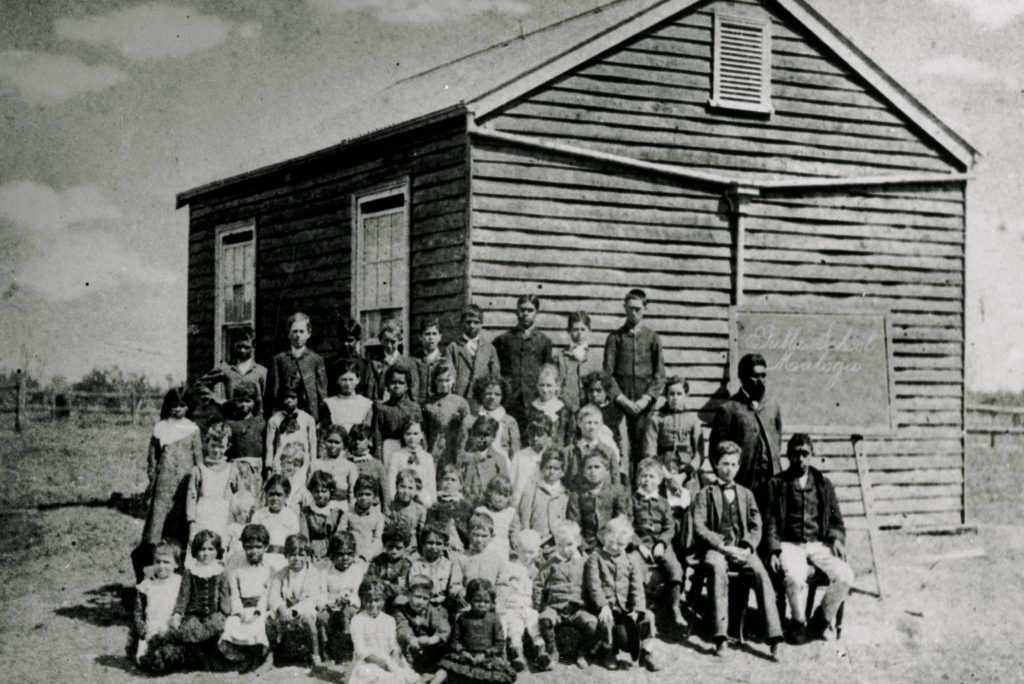

Thomas Shadrach James joined Maloga as a teacher in 1881. As the member of another subject race — he was born and raised in the British colony of Mauritius — he was sympathetic towards the plight of the Aboriginal people. At Maloga they came to regard him as kin, which was cemented when he married Cooper’s sister Ada. At the mission James taught the men as well as the children, urging the former to embrace the opportunities he believed were provided by British civilisation but also assert their rights as British subjects. He taught several men who went on to play a major role in the fight for Aboriginal rights: Doug Nicholls, Jack Patten, George Patten, Bill Onus, Eric Onus, and his eldest son, Shadrach Livingstone James.

The July 1887 Petition

In July 1887 Cooper was one of about a dozen men associated with Maloga to sign a petition, which one of his brothers soon presented to the Governor of New South Wales. Almost certainly prepared on their behalf by Thomas Shadrach James, the petitioners called for sections of land of no less than 100 aces to be granted to each family. They argued this would enable them to earn their own living. At the same time, they pointed out that ‘the Aborigines were the former occupiers of the land’.

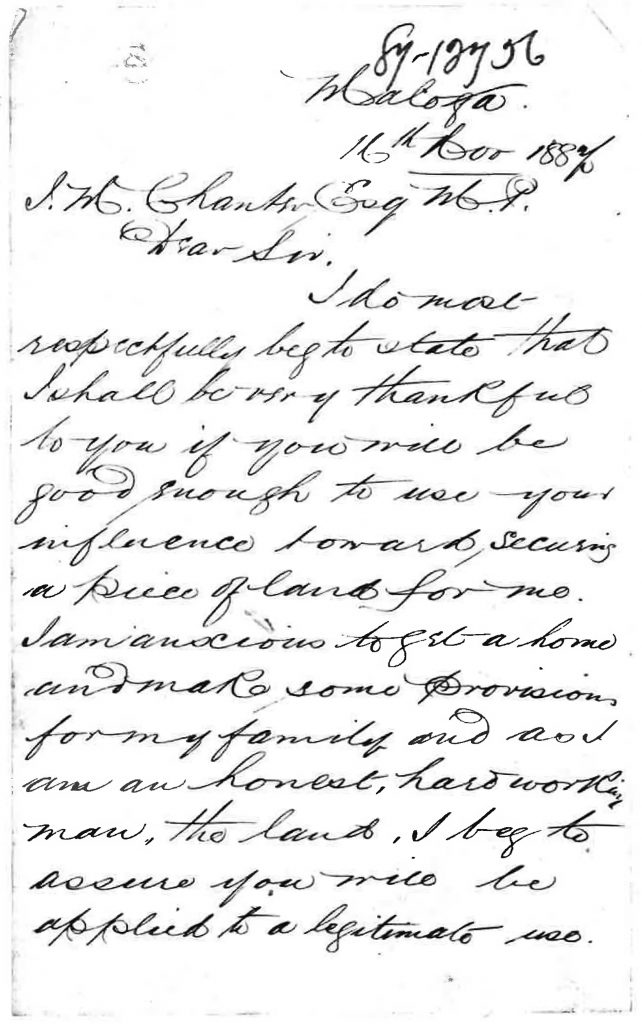

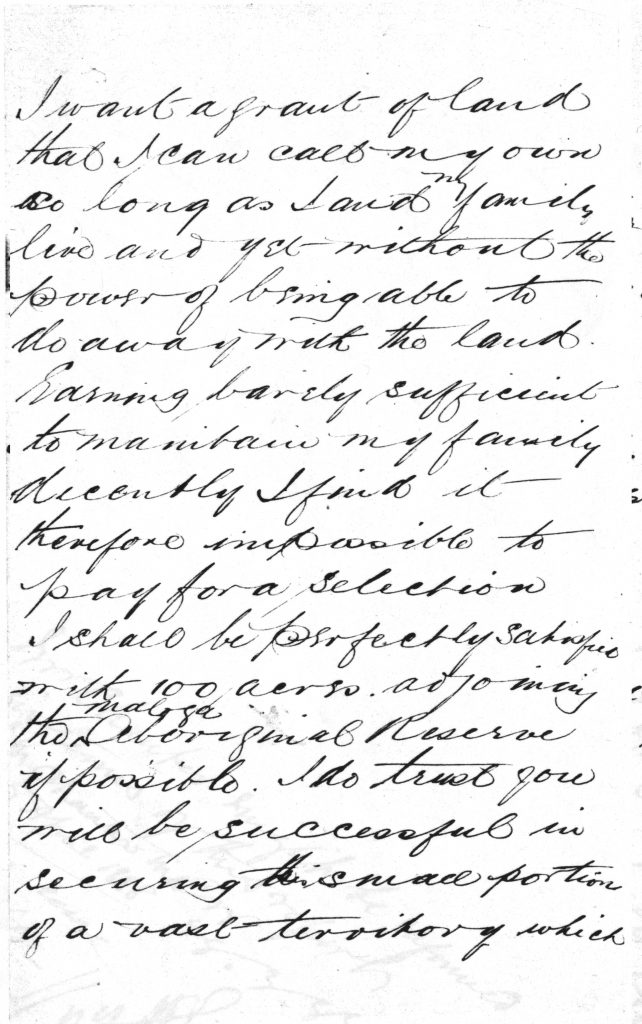

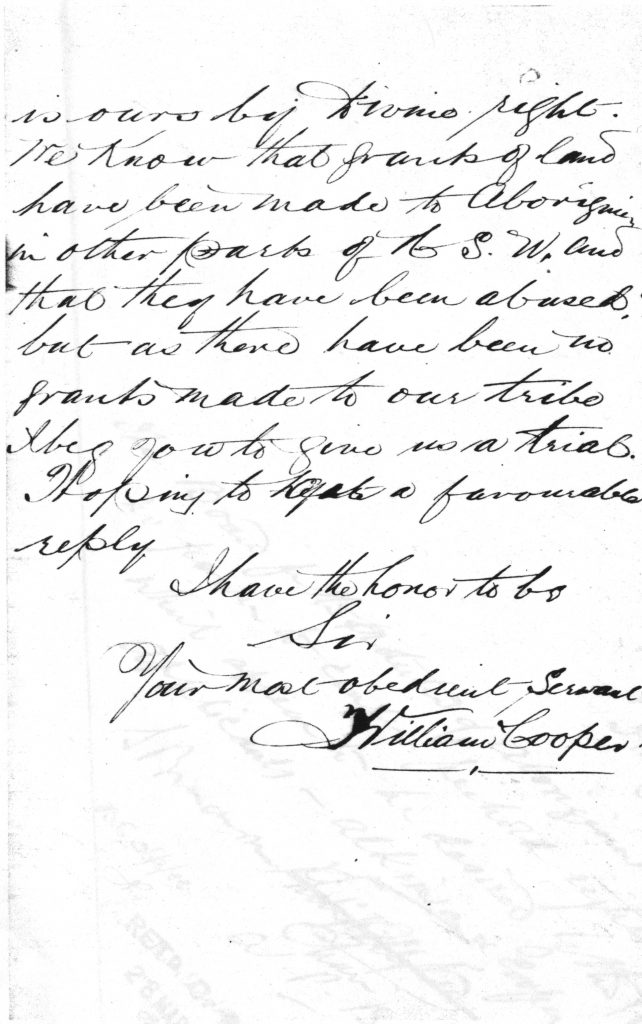

In November the same year Cooper and his brother Johnny Atkinson, assisted by James, wrote to the local member of parliament, John Chanter, asking him to use his influence to help them obtain pieces of land adjoining Maloga. Both men reiterated the request made in the petition. Cooper asserted he was only seeking ‘a small portion of a vast territory’ that was the Aboriginal people’s ‘by divine right’. In doing so, he used the language of the religion he had adopted but the authority he invoked had a traditional Aboriginal source. Like earlier Aboriginal petitioners for land, Cooper was insisting that the government recognise a right that rested on the Aboriginal people’s prior ownership of the country.

Cooper’s letter to Chanter, 16 November 1887, New South Wales Archives and Records