The Day of Mourning

(1938)

The idea

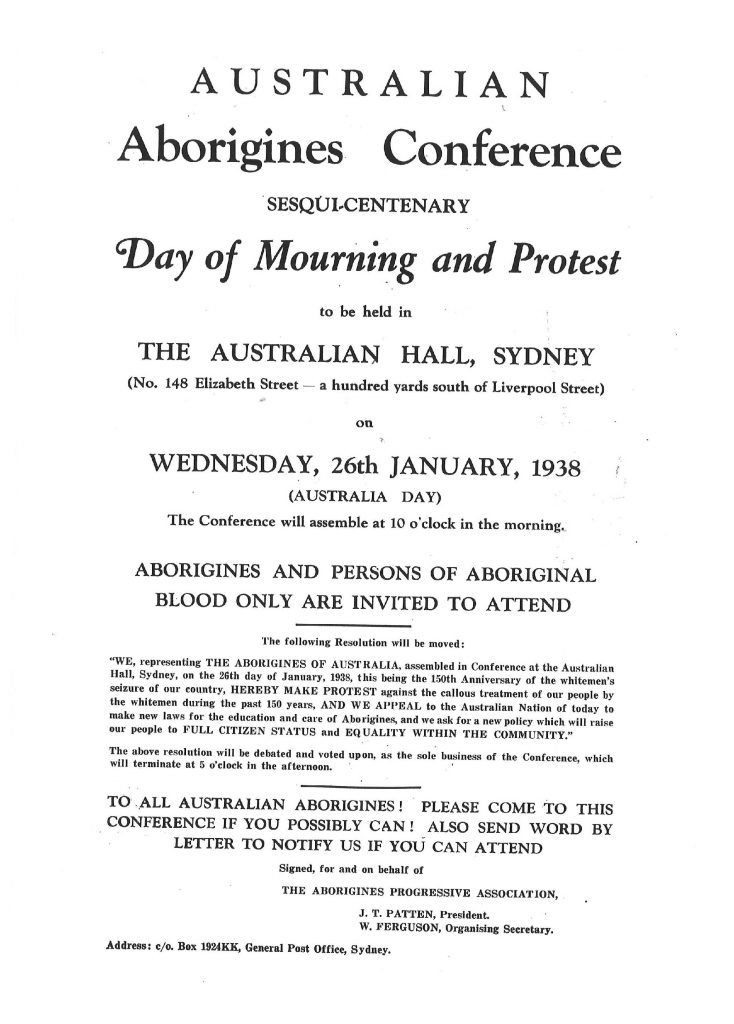

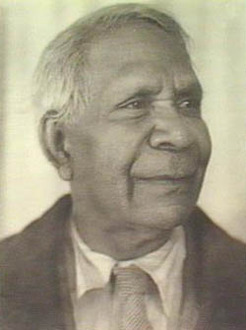

Cooper’s name is often connected with the Aboriginal Day of Mourning, which took place in Sydney on 26 January 1938 in order to protest against the sesquicentenary celebrations of white settlement in Australia. Cooper proposed this action during a meeting of the Australian Aborigines’ League in November 1937 that was attended by the secretary of the Aborigines Progressive Association, William (Bill) Ferguson. Arthur Burdeu informed the press: ‘While white men are throwing their hats into the air with joy, aborigines will be in mourning for all that they have lost’.

The idea of the Day of Mourning owned much to Cooper’s historical sensibility. Like other Yorta Yorta people, he had a prophetic view of history, derived from the biblical stories they had been told by the missionary Daniel Matthews. This envisaged a relationship between past, present and future as a long trajectory marked by epochs and days — of Judgement and Restitution, of Mourning and Hope — at the end of which there would surely be deliverance for Aboriginal people from the suffering they had experienced since the coming of the white man.

The planning

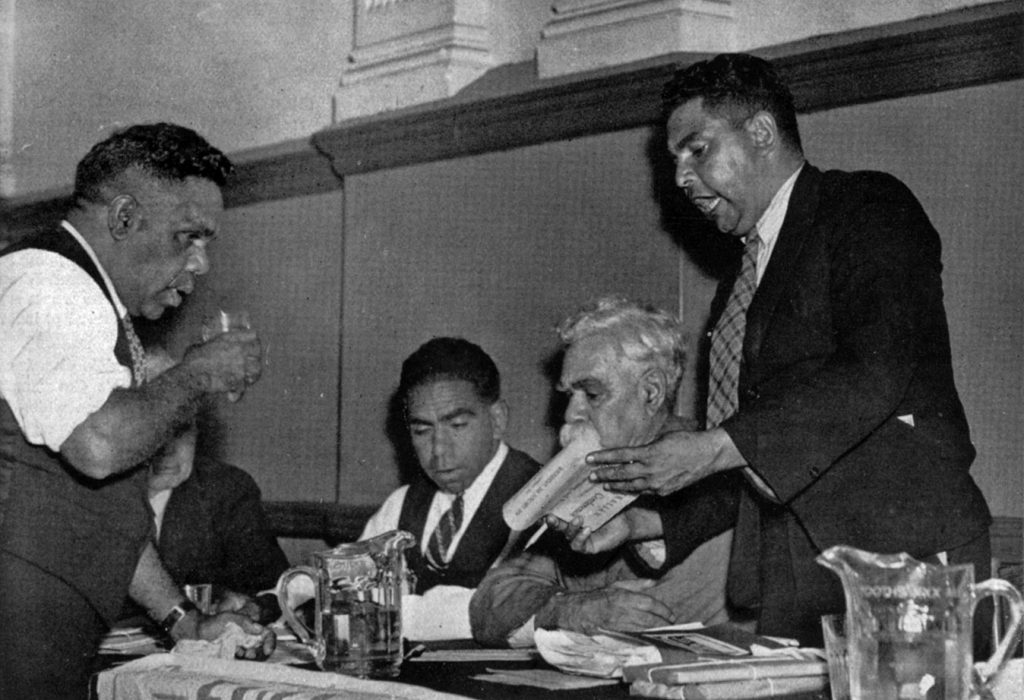

After Cooper and Ferguson agreed to stage a day of mourning, the Aborigines Progressive Association took charge of organising it, so much so that Cooper came to see the day as the Association’s. Nevertheless, he fiercely defended it after it was attacked by David Unaipon, a South Australian preacher, author and inventor, who was closely associated with a white clergyman J. H. Sexton and the Aborigines’ Friends Association and who might have been the best-known Aboriginal person in Australia at this time.

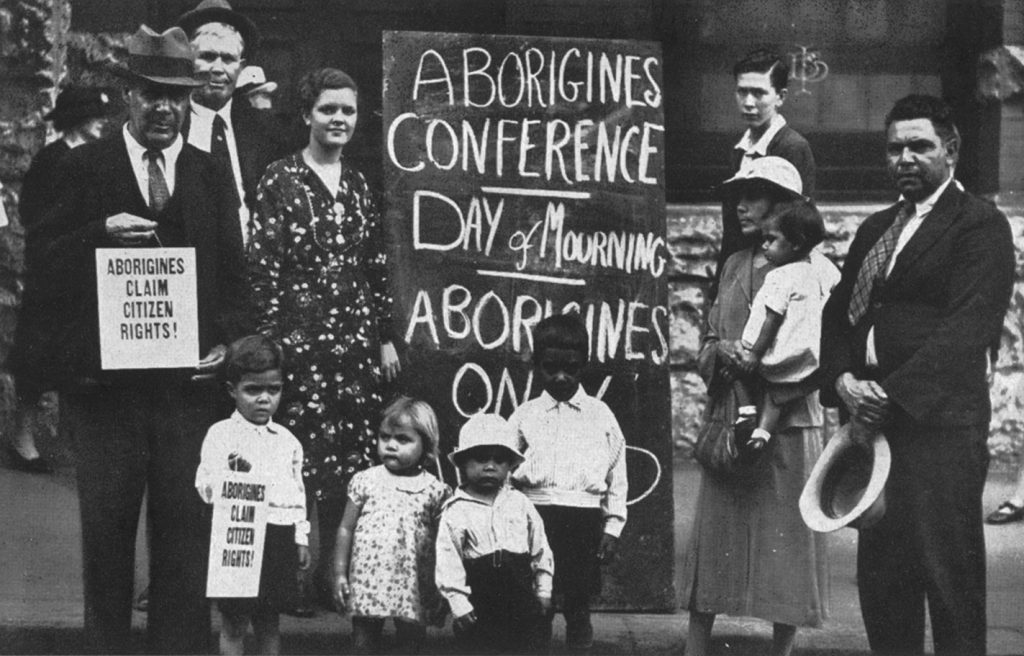

Cooper and his two acolytes, Doug Nicholls and Margaret Tucker, attended the Day of Mourning. Helen Baillie drove them there in her little car, driving at breakneck speed for much of the treacherously narrow and sometimes twisting Hume Highway. They arrived shaken but just in time to attend a meeting that passed a resolution condemning the New South Wales government for coercing Aboriginal people from the Menindee reserve in far-west of the state to participate in the celebrations that were take place the following day.

The event

On the morning of 26 January, from a street near the Town Hall, Cooper, Nicholls and Tucker watched a procession of floats that was part of a series of events in the city and on the harbour celebrating 150 years of white settlement, and then made their way to the Australian Hall for the Day of Mourning protest meeting that took place that afternoon.

Cooper, Nicholls and Tucker were to play relatively minor roles in its proceedings, which were dominated by Ferguson and Patten. Cooper encountered opposition to the grounds upon which his call for Aboriginal parliamentary representation was seen to rest, namely special rights for indigenous people.