Cooper’s Last Years

(1939-1941)

By the time the Cumeroogunga walk-off had run its course, Australia was becoming embroiled in another overseas war. This gave the Australian Aborigines’ League and other Aboriginal political organisations an opportunity to press their demand for citizenship rights.

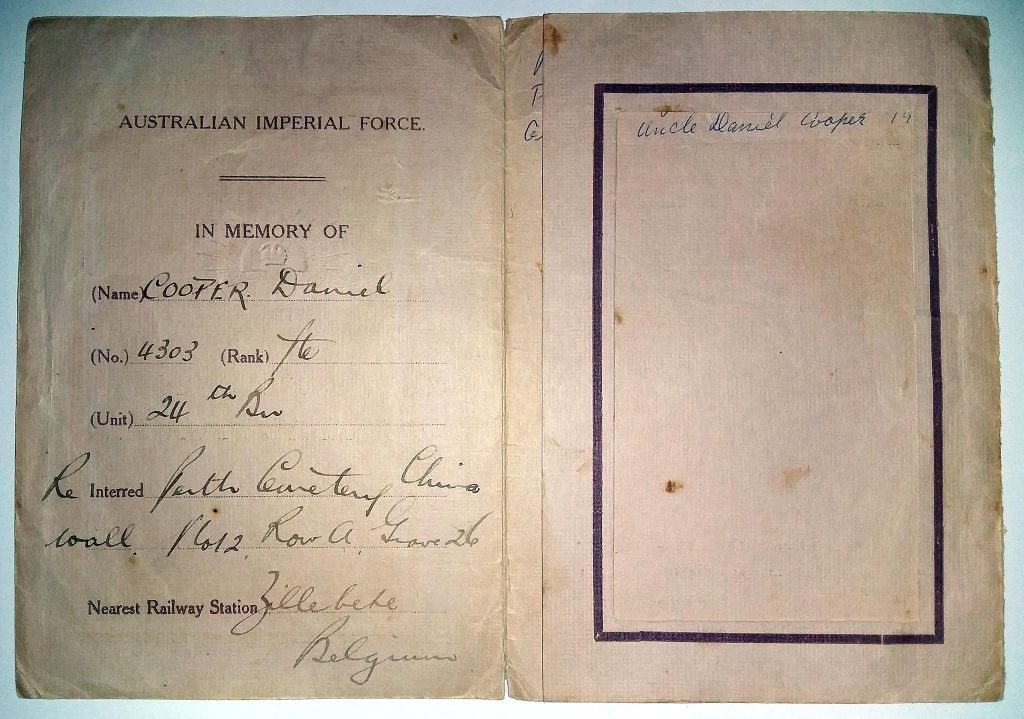

In February 1938 Arthur Burdeu, as the President of the League, suggested to the federal government that an Aboriginal citizen corps be formed, thereby making a connection between military service and a right to citizenship. But in January the following year William Cooper reversed the League’s position and drew into question whether Aboriginal men should fight for Australia given that they had, in his words, ‘no status, no rights, no land’. Military service was a deeply personal matter for him, having lost his son Daniel in the Great War. He contended that the enlistment of Aboriginal men should be conditional upon their being granted citizenship before they went to war, remarking: ‘They were wanted to fight to make Australia safe for those who took it from the natives’.

War and liberty

Soon after the war began, Cooper seized the opportunity to make the case for citizenship rights. In a letter he sent to Prime Minister Robert Menzies he invoked his status as the father of a son who had died alongside his white comrades ‘in the cause of liberty’ and argued that, since Australia was involved in a war in which it was fighting for the rights of minorities, the government had to make sure that it granted rights to its minority, the Aboriginal people. In December 1939 he made this point again in another letter to Menzies, arguing that the war was being fought ‘by reason of the tyranny over minorities and their cruel discriminating treatment’ and so Australia could not ‘fight that cause in honesty while still oppressing her minority’.

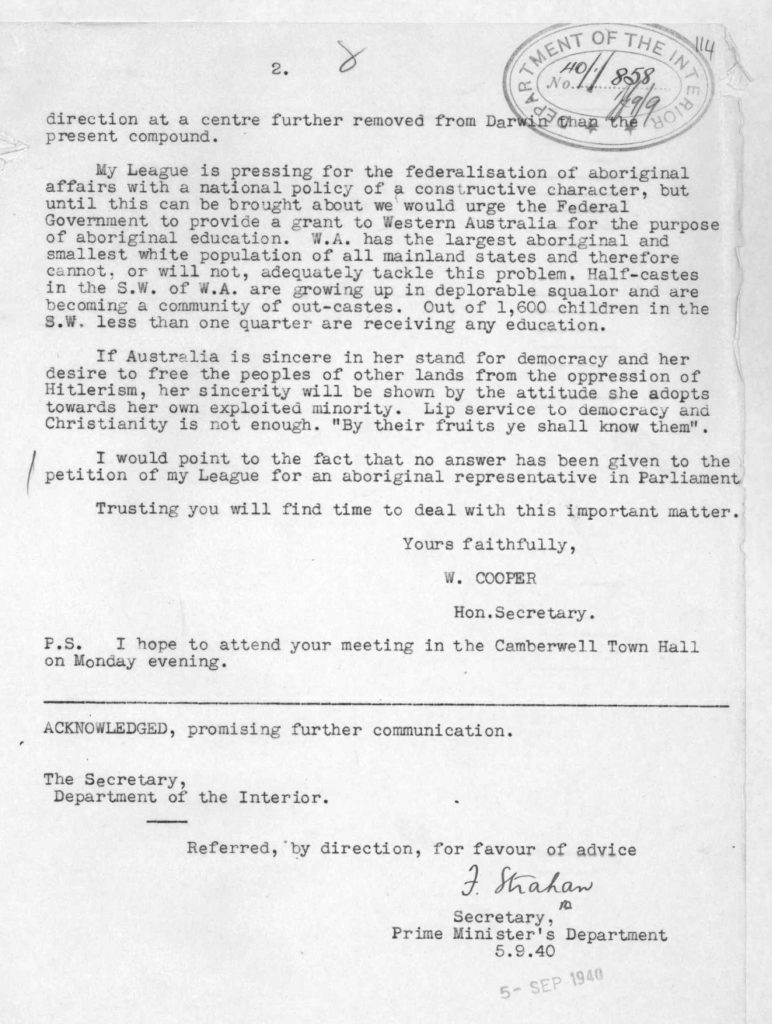

In August 1940, in the last letter he ever sent as the League’s secretary, Cooper raised with Prime Minister Menzies the matters he had broached several months earlier. ‘If Australia is sincere in her stand for democracy and her desire to free the peoples of other lands from the oppression of Hitlerism’, he asserted, ‘her sincerity will be shown by the attitude she adopts towards her own exploited minority. Lip service to democracy and Christianity is not enough. “By their fruits ye shall know them”.

Final days

By November 1940 Cooper must have known his long life was drawing to a close as he stood down as the secretary of the League. Shortly afterwards he returned to his own country, where he died a few months later. He was buried in the cemetery at Cumeroogunga after a service that was conducted in the church by one of his family, Eddy Atkinson, and a prayer read at his graveside by Doug Nicholls, who was to become his political heir. Many people came to pay their last respects. The Melbourne newspapers remembered Cooper for his remarkable petition to the King.