Cumeroogunga Reserve

(1888–1920s)

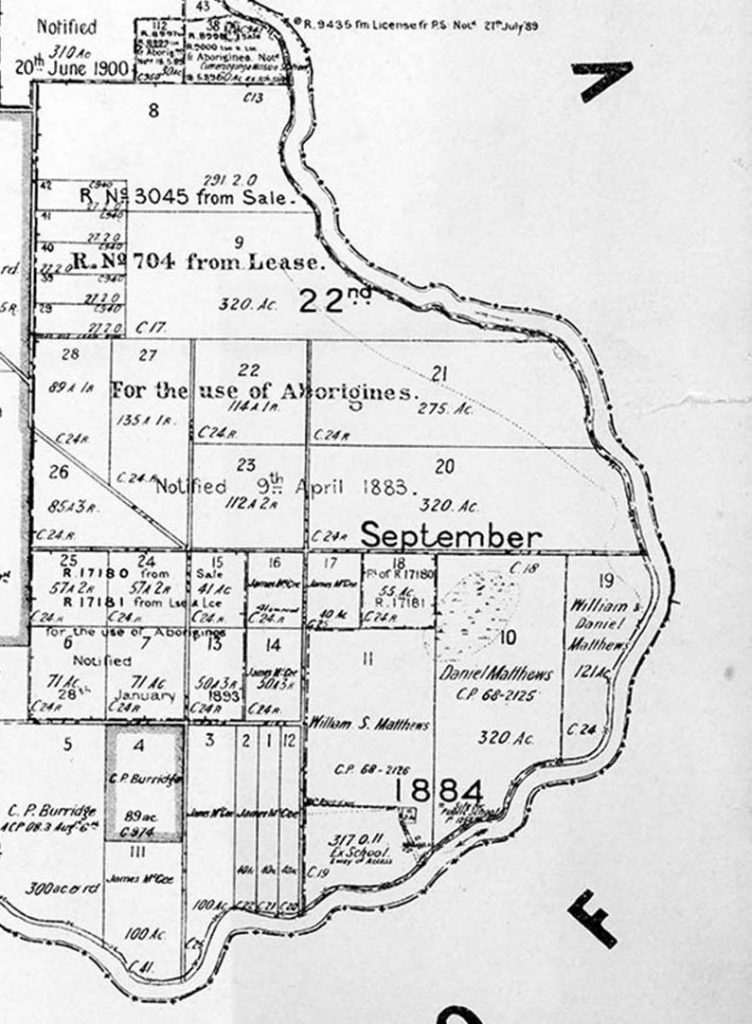

By the mid-1880s there was considerable tension at Maloga. The Aboriginal men increasingly challenged Matthews’ authority, expressing a wish to be free and independent of his paternalistic rule. In particular they wanted control over the land for which they had first petitioned government in 1881. Furthermore, the Aborigines Protection Association, a powerful philanthropic organisation in Sydney, wanted to resolve a matter that had troubled it since becoming the mission’s sponsor. In 1887 it tried but failed to negotiate a transfer of the title to the land from the Matthews family. Consequently, it directed George Bellenger, whom it had recently appointed to replace Matthews as Maloga’s superintendent, to shift the mission to an adjoining piece of land that the colonial government had reserved for Aboriginal use in 1883.

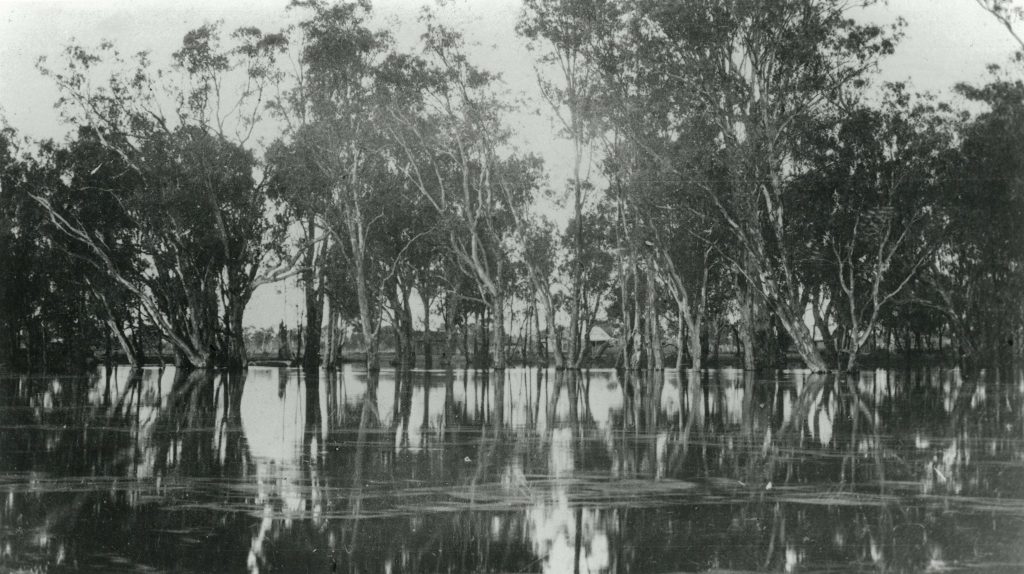

Many of the Aboriginal people welcomed the end of Matthews’ rule at Maloga. The men looked forward to being able to subdivide the reserve into blocks for their families and farming them. But the Aborigines Protection Association was initially unable to secure a suitable site for the mission. The shift there in mid-1888 was botched. As a result, while a new Yorta Yorta name was bestowed on it — Cumeroogunga, meaning ‘our home’ — its beginnings were far from home-like. In December that year some of the people contracted typhoid fever when they travelled to the Melbourne suburb of Brighton for an annual religious camp. Shortly after returning home, Cooper’s infant son died while his wife Annie succumbed to the illness at the Bendigo hospital shortly afterwards.

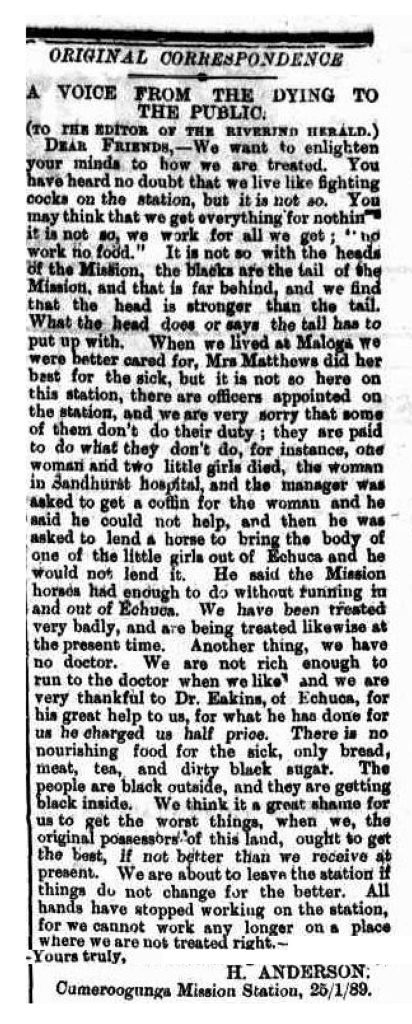

In the thick of the epidemic the people found George Bellenger an uncaring and unsympathetic superintendent. He refused to lend Cooper a cart to bring Annie’s body home so she could rest in peace in her own country. A local doctor was outraged by his neglect. The people also learned that Bellenger was more authoritarian than Matthews had ever been and they were quick to protest. One of their number, Hugh Anderson, sent two letters to the local newspaper on their behalf and drew up a petition, to which Cooper was almost certainly a signatory. One of their complaints concerned the distribution of rations: ‘We have always understood the government having dispossessed us of our land, hunting grounds, &c., gave us rations as compensation’.

Recovery

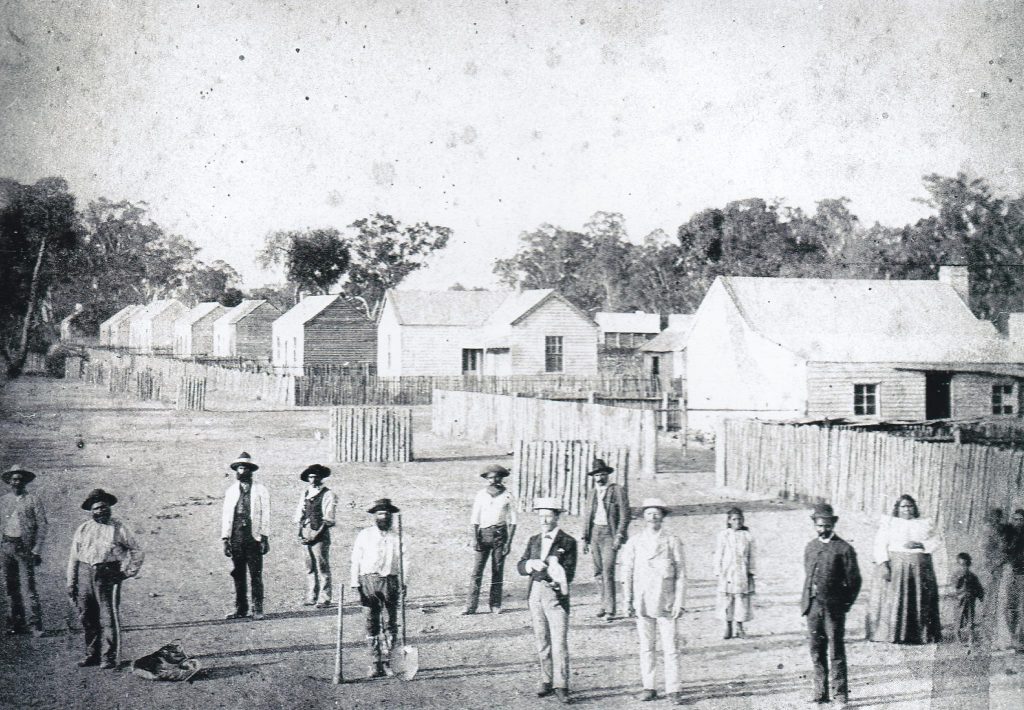

After this distressing and dispiriting beginning, the men set to work, laying out streets, planting trees, reconstructing the cottages, erecting new buildings, clearing land and planting crops. As a result, the mission began to recover. Twenty of the men, of which Cooper was no doubt one, were soon granted blocks of land by the Aborigines Protection Association and eagerly set about farming them. They only comprised 20 acres, but the men were able to supplement the income they derived from them with wages they earned on nearby pastoral properties while the women could fish in the Murray and cultivate vegetables and fruit on the mission. The blocks provided them with a degree of independence and the Association assured them of their tenure.

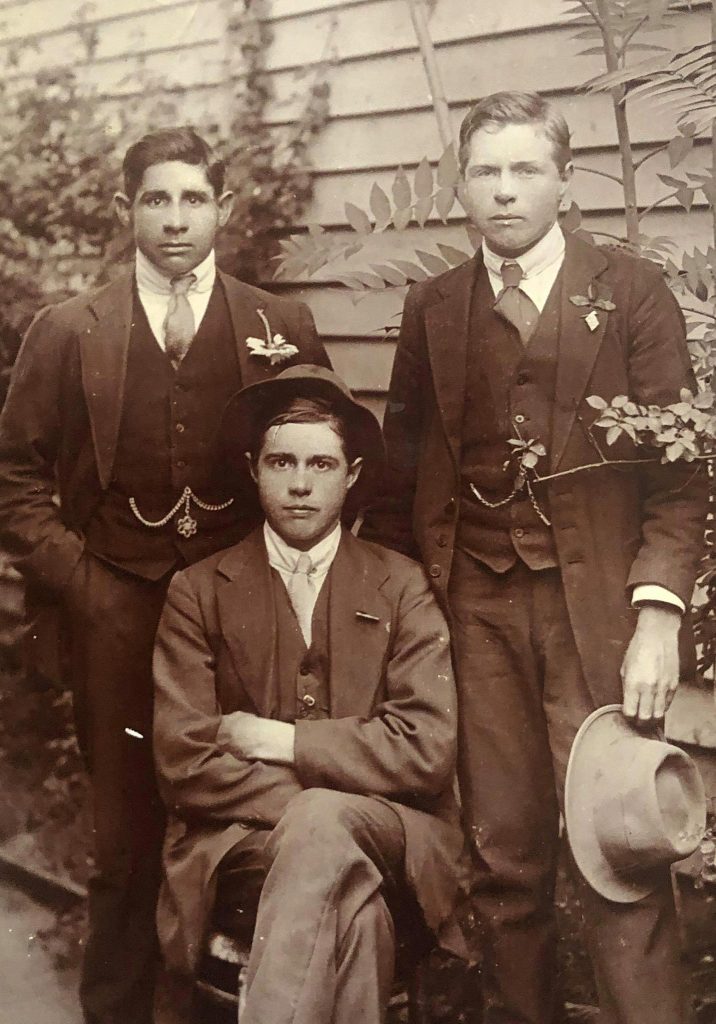

In 1893 Cooper remarried. His wife, Agnes Hamilton, was a Taungurung woman from the northern Riverina, but had grown up on a Victorian reserve. In the next seventeen years they had seven children together, six of whom survived infancy. Pictured here is Amy on Agnes’ knee; Daniel to her left; Jessie and Gillison on her right; and William’s daughter from his first marriage, Emily, behind her. Like many of the men, Cooper had to seek seasonal work in the district and elsewhere as a fisherman, shearer, drover, horse-breaker and general rural labourer. As a member of the Shearers’ Union and the Australian Workers’ Union, it is believed that he became a spokesman for Aboriginal workers in central Victoria and western New South Wales.

Exile

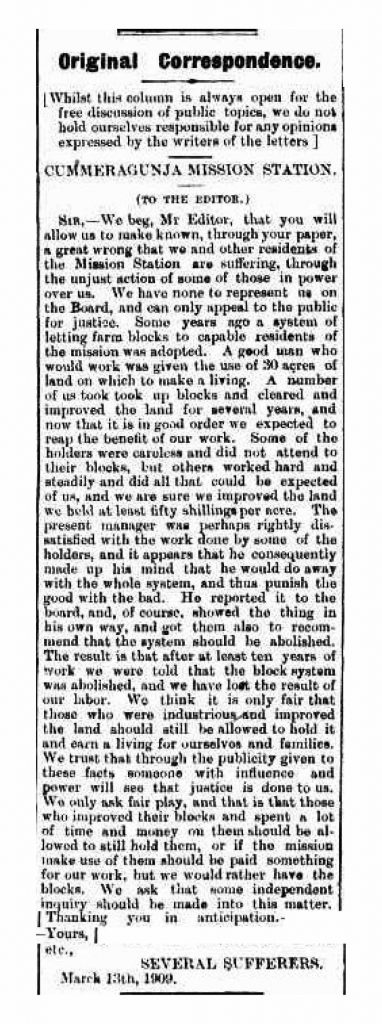

Despite Cumeroogunga’s progress, it suffered fundamental problems that all Aboriginal reserves suffered: a lack of good land and sufficient capital to develop it. Adding to these woes, the reserve fell under the control of a special body that oversaw Aboriginal affairs in New South Wales (as was the case in each of the Australian states except Tasmania). In the 1900s the New South Wales Board for the Protection of Aborigines abolished the farm block system on the reserve and forced the men to work as wage labourers under a white overseer. This was bitterly resented by the people. They made representations in the local newspaper, drew up a petition to the district council, and engaged a lawyer, pointing out that ‘a grave justice’ had been done and calling for an independent tribunal to conduct a comprehensive public inquiry.

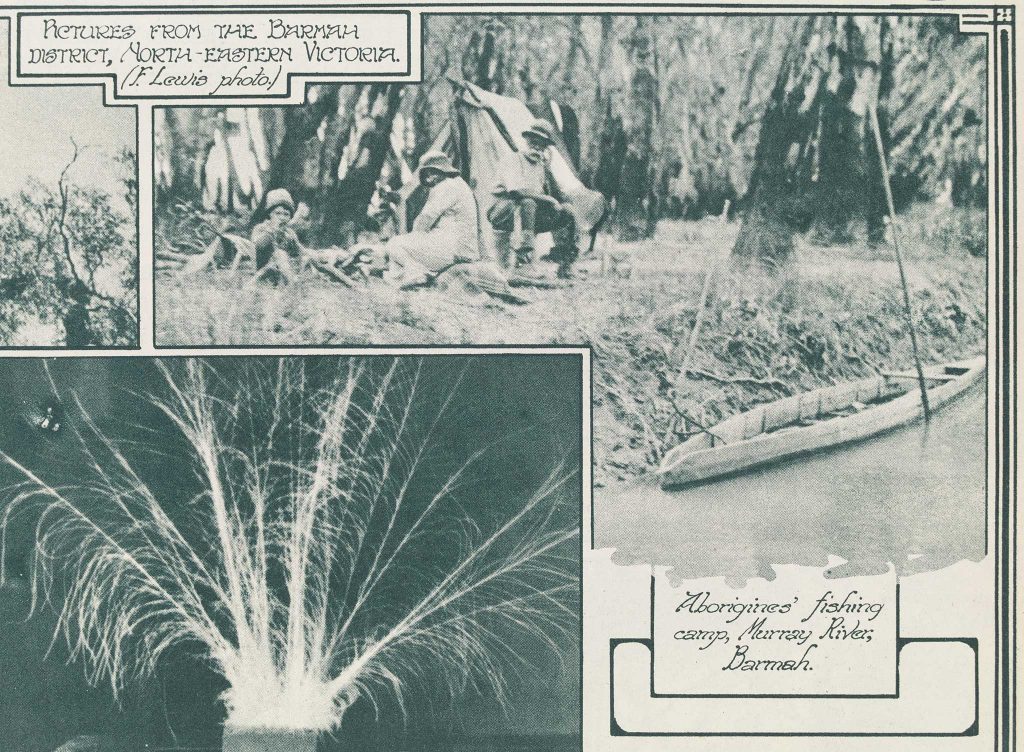

A series of confrontations took place at Cumeroogunga over the matter of the farm blocks, and the manager, George Harris, expelled many of the men as ‘troublemakers’. Cooper was among those who were driven off the reserve or who left of their own accord in the late 1900s because they could not abide the way they were being treated. Cooper took his family across the river and made a house for them at Barmah, as did many others, including Thomas and Ada James. Cooper never returned to Cumeroogunga. But in April 1909 he suffered an awful blow. Agnes died suddenly, having, like many Aboriginal people, contracted tuberculosis. By this time their older four children were in their teens but the two youngest, Lynch and Sally, were barely four and two years old respectively.

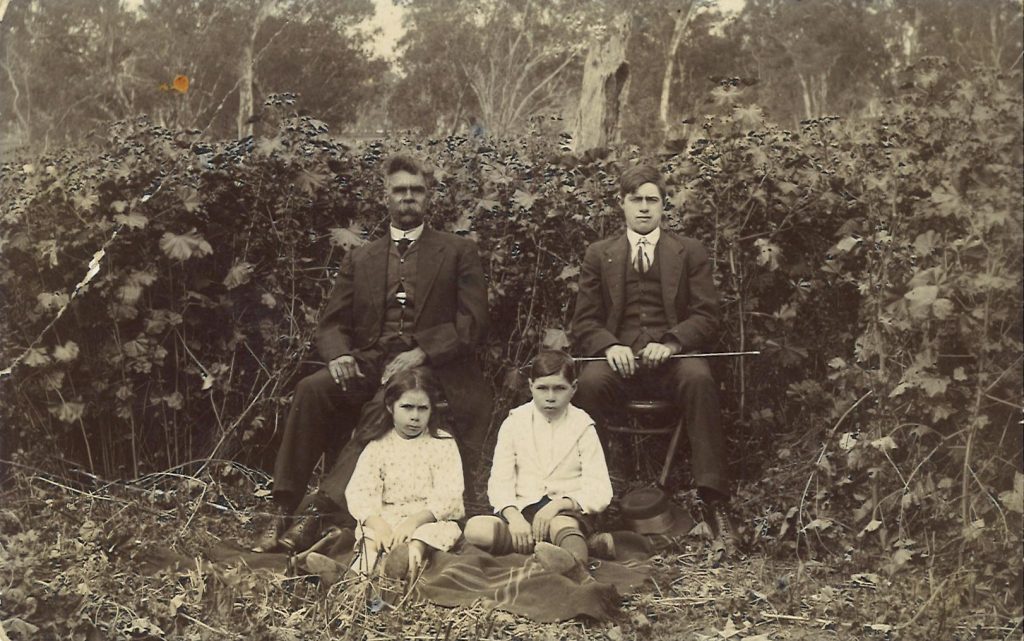

It seems that Cooper spent most of the 1910s and 1920s at Mulwala and Yarrawonga, working as a labourer and a fisherman. During this period the New South Wales Board for the Protection of Aborigines forced many Aboriginal people of so-called ‘mixed descent’ off reserves such as Cumeroogunga and removed some of their children and sent them to special Aboriginal children’s homes or into apprenticeships or service. Cooper did not fall victim to the latter policy (though those of his kith and kin who remained at Cumeroogunga did), perhaps because he was able to secure the services of a young Aboriginal woman, Sarah Nelson (nee McCrae), to care for Lynch and Sally, who are pictured here with William, Sarah and an older woman, who is probably Agnes’ mother, Annie Hamilton.

Loss

While Cooper was able to keep his young family together during these years, he nonetheless suffered a series of personal losses. Two of his brothers, Johnny and Aaron Atkinson, died in 1910 and 1913 respectively. In 1913 his eldest daughter, Emily Dunolly, died, like Agnes, of tuberculosis, leaving behind a husband and two young children. Most tragically, in 1917 William’s eldest son, Daniel, whom he had named after his missionary mentor, was killed in action at Ypres in Belgium while serving in the AIF. Five years later, William and Agnes’ first-born child, Jessie Mann, died in Condoblin in New South Wales of peritonitis shortly after giving birth to her third child, leaving behind a husband, the baby and two other youngsters.

Consolation

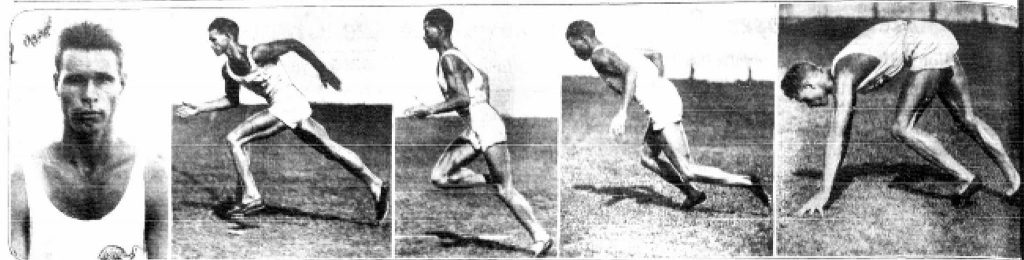

One of the few bright spots in Cooper’s life during these years was the sporting success of his youngest son, who was at his peak as an athlete. Lynch was a good Australian Rules footballer but running was his real forte. He won several prestigious sprint events: the Warracknabeal Gift in 1926, the Stawell Gift in 1928, and the World Sprint Championship in 1929. In fact he ran professionally for more than twenty years, competing throughout Australia as well as in New Zealand. Cooper encouraged him to compete — Lynch once joked that he had been ‘chased into the footrunning business by his father’ — and since was no slouch himself as a runner and hurdler William was able to give his son some hints early in his career.

In 1928 William found another source of solace, marrying for a third time. His wife, Sarah Nelson (nee McCrae), had been born at Wahgunyah in about 1881. Soon afterwards they made a home together at Barmah, next door to other Aboriginal families in exile from Cumeroogunga, and assumed responsibility for more than one of his grandchildren. By this time William was probably receiving the old-age pension, which the federal government granted to some Aboriginal people of ‘mixed descent’ so long as they did not reside on an Aboriginal reserve. He also received a war pension by dint of the fact that he had a lost a son (Daniel), in the Great War, though even when he put together the two pensions they did not amount to much.