Cooper’s Political Work Begins

(1933–35)

The move to Melbourne

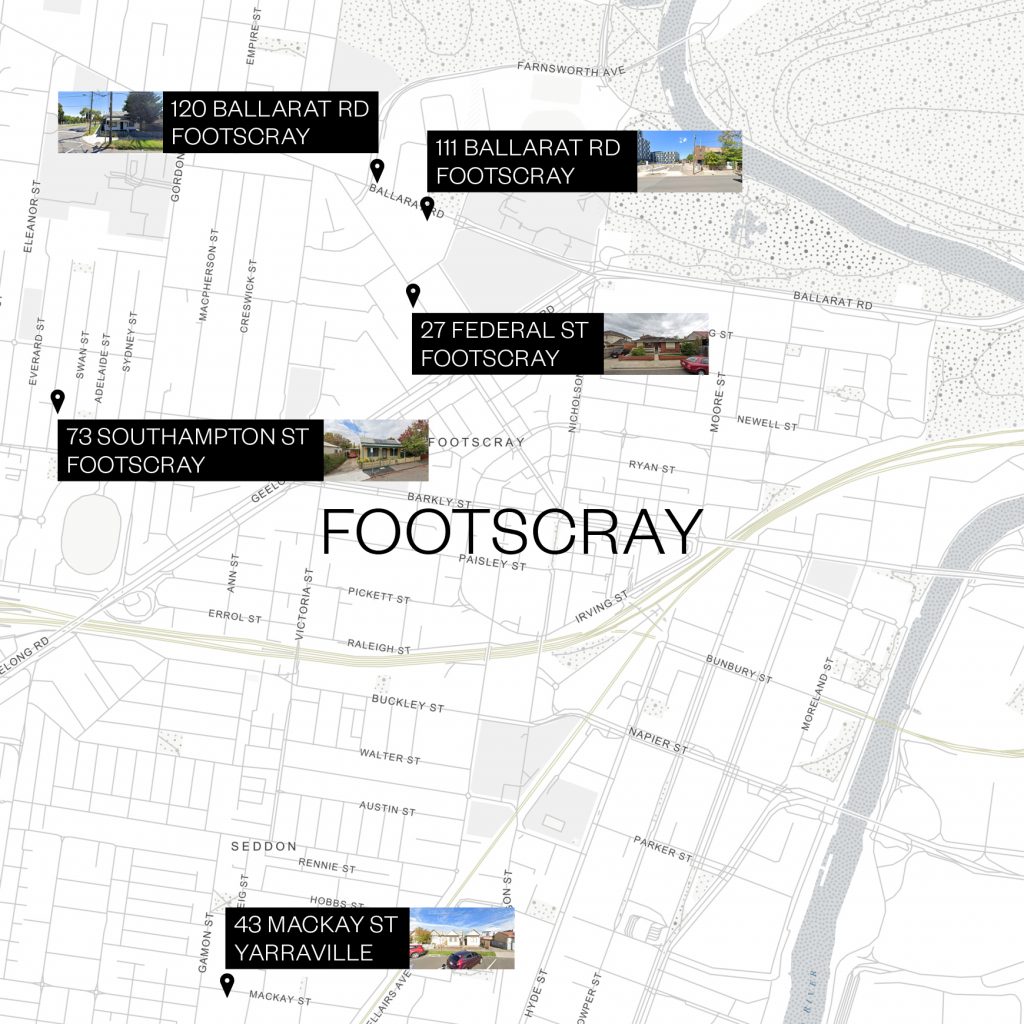

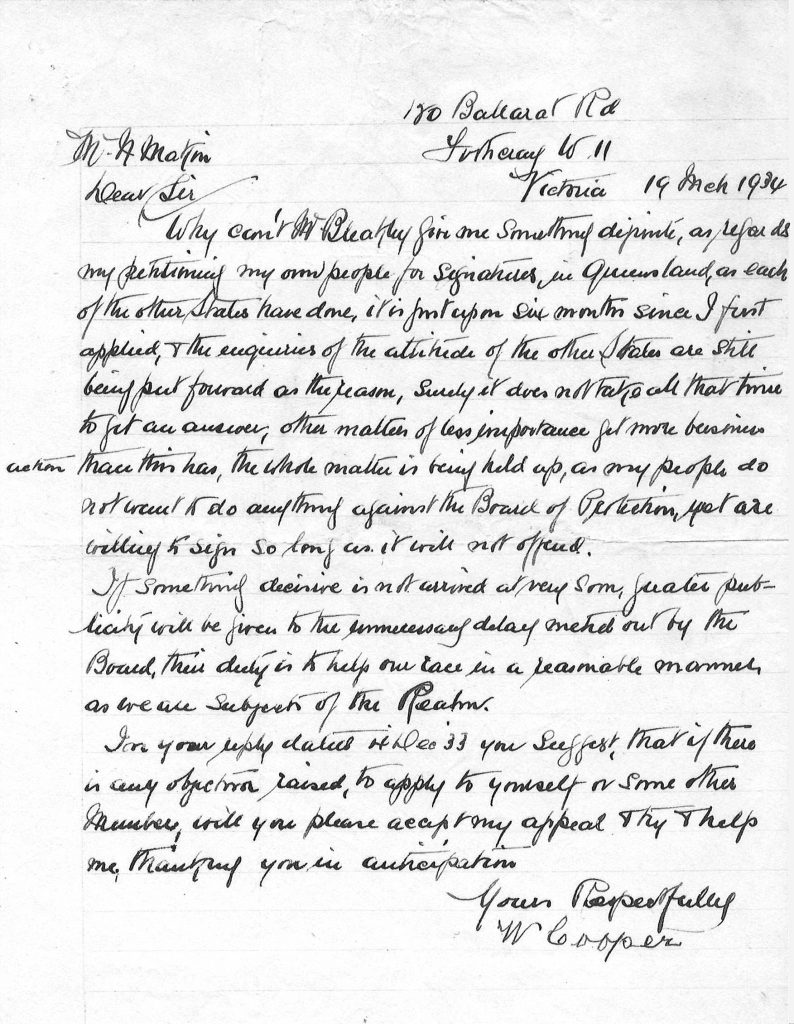

In 1933 Cooper decided to move to Melbourne so that he could take up the cause of his people by drawing on the resources only a large city could provide him with. He and Sarah spent the next seven years there, renting a series of houses in the working-class suburbs of Footscray and Yarraville. Between July 1933 and November 1934 they were living in a room at 120 Ballarat Rd, Footscray, which was probably a boarding house at the time. By March 1935 they had moved to 27 Federal St, Footscray. In May 1937 they were living at 111 Ballarat Road, Footscray, but in the following month they moved to 43 Mackay St, Yarraville. They remained there until January 1938, at which point they moved to 73 Southampton St, Footscray, where they remained for the duration of their years in Melbourne. Members of the Australian Aborigines’ League later recalled meeting in one of these houses, huddling around the fire in its front room, two candles flickering on the mantlepiece.

In 1933 Cooper decided to move to Melbourne so that he could take up the cause of his people by drawing on the resources only a large city could provide him with. He and Sarah spent the next seven years there, renting a series of houses in the working-class suburbs of Footscray and Yarraville. Between July 1933 and November 1934 they were living in a room at 120 Ballarat Rd, Footscray, which was probably a boarding house at the time. By March 1935 they had moved to 27 Federal St, Footscray. In May 1937 they were living at 111 Ballarat Road, Footscray, but in the following month they moved to 43 Mackay St, Yarraville. They remained there until January 1938, at which point they moved to 73 Southampton St, Footscray, where they remained for the duration of their years in Melbourne. Members of the Australian Aborigines’ League later recalled meeting in one of these houses, huddling around the fire in its front room, two candles flickering on the mantlepiece.

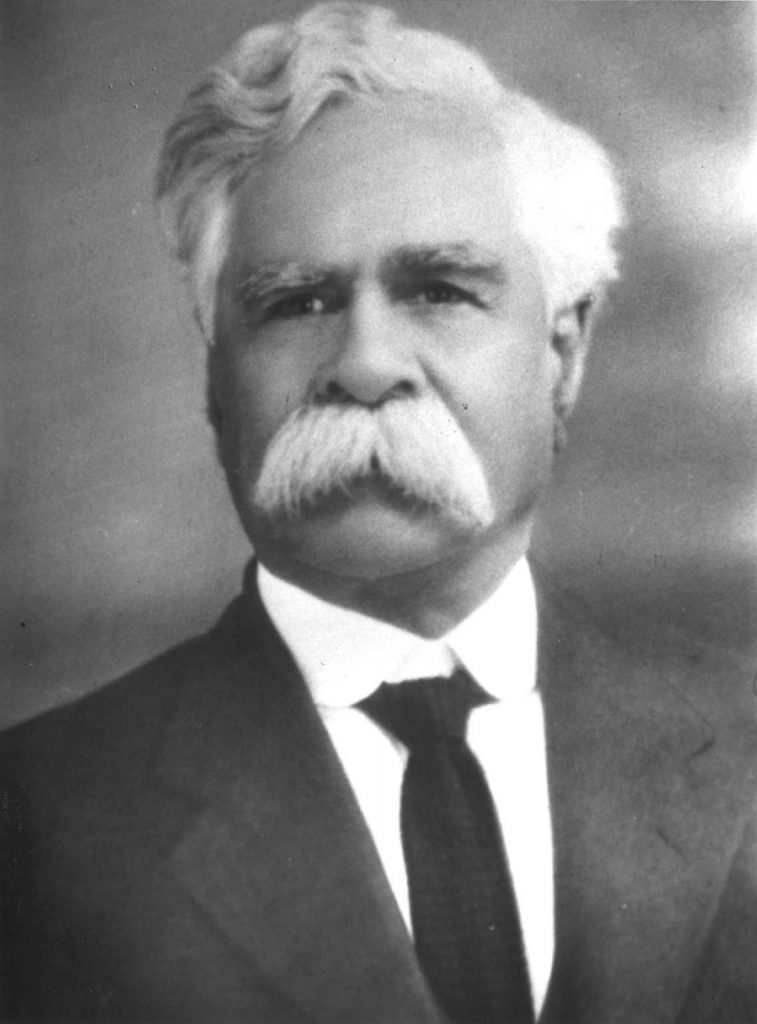

The Coopers struggled to make ends meet. At various times they had under their roof Cooper’s daughter Jessie’s three children and his daughter Amy’s son, Alf (Boydie), so that they were not taken by white authorities and placed in a children’s home. At some point they also looked after Cooper’s son Gillison’s twin sons in the hope that William could provide them with some discipline. To save money for the cause, Cooper seldom rode in a tram or train but walked everywhere instead. In this photograph he is striding down Nicholson Street, the main shopping street in Footscray. One of the Cooper family later captioned this photograph ‘Pup Cooper’. In these years he was regarded as a father figure by Aboriginal community in Melbourne which numbered a hundred or so people, most of whom lived in Fitzroy.

Beginning his political work

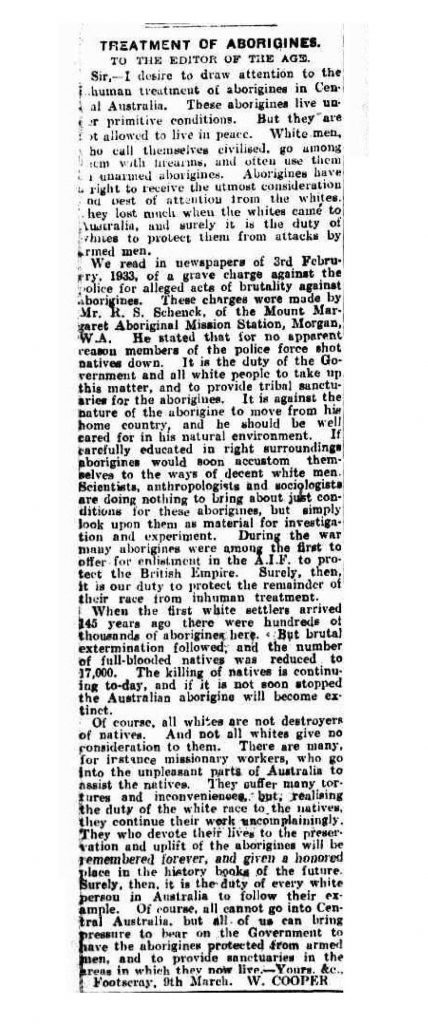

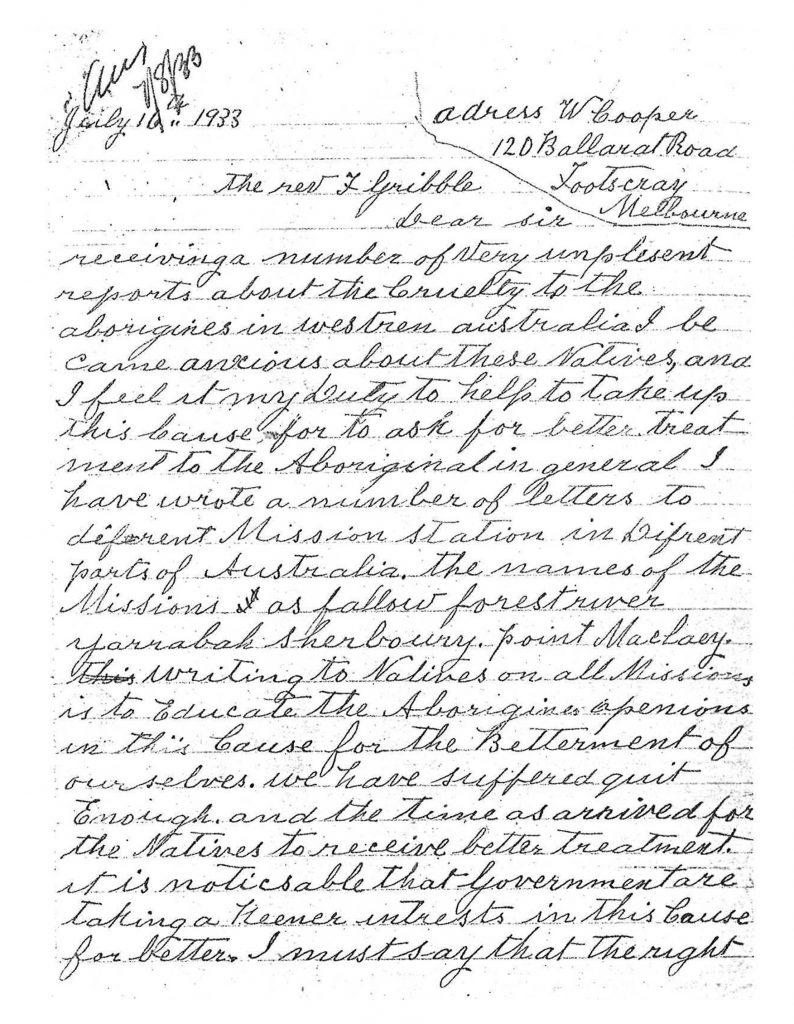

In March 1933 Cooper began his political campaign by sending a letter to the editor of The Age, after reading a newspaper article that had reported claims a missionary had made about the indiscriminate shooting of Aboriginal people by the police force in north-west Western Australia. As Cooper commented to another missionary, Rev. Ernest Gribble, a few months later, ‘We have suffered quit[e] enough and the time has arrived for the natives to receive better treatment’.

Shadrach James

In taking up his political work, Cooper was both anticipated and influenced by his nephew, Shadrach Livingstone James, the eldest son of Cooper’s sister Ada and Thomas James. In 1929 and 1930 James had raised his voice on behalf of Aboriginal people, speaking to missionary organisations, writing to a federal minister, and making appeals to the labour movement. Like Cooper, most of James’ protest was informed by his own experience or that of his family and kin at Maloga and Cumeroogunga as well as by his connections to the union movement. It also probable that James was influenced by his father’s ongoing connections to India, Mauritius and the Indian diaspora and thus to both the anti-colonial struggle in India and the campaigns against indentured labour in other British colonies like Fiji.

This photograph of Shadrach James illustrated a newspaper report about his political advocacy that appeared in a Melbourne newspaper that was sympathetic to the plight of Aboriginal people. Herald (Melbourne), 1930

Shadrach James also assisted Cooper in the early years of his campaign by writing letters on his behalf. ‘[M]y education is not what I would like it to be’, Cooper confessed to a missionary; ‘it seems a struggle for me to keep up to the standard I ha[d] got the work up to’. The differences between Cooper and Shadrach James’ penmanship can be seen in the two letters above.

Helen Baillie

In beginning his political work in Melbourne, Cooper was able to draw on the assistance of several white people, just as he had hoped. By far the most important of these men and woman was Helen Baillie. Single, middle-class and financially independent, she was a fervent Christian and a committed socialist who embraced many causes. Cooper must have quickly grasped that Baillie was an invaluable source of information about the relevant agencies and officials in Aboriginal affairs in the federal government and that she was willing to put him in touch with white men who could help him in his cause, such as the firebrand missionary Ernest Gribble and Rev. William Morley who was the secretary of a white organisation, the Association for the Protection of Native Races

Baillie was instrumental in organising a meeting between Cooper’s organisation and white supporters (such as William Morley) on the one hand and the federal Minister for the Interior, Thomas Patterson, on the other. The deputation struck several newspapers as novel simply because it included Aboriginal men and women. It was probably the first time Aboriginal people had ever waited on a federal government minister