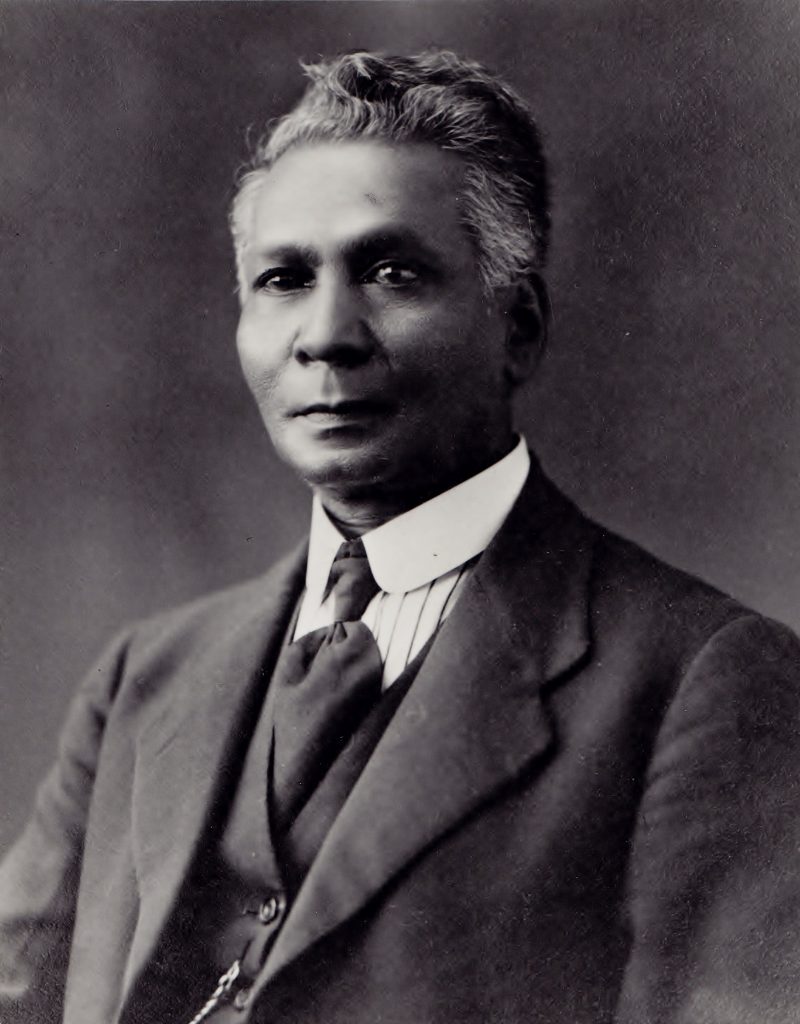

Thomas Shadrach James

(1859–1946)

Thomas Shadrach James played a significant role in the life of Maloga Mission and its successor, Cumeroogunga, and that of its people, not least of whom was Cooper.

Born in 1859 in Port Louis, the capital of Mauritius, a small British colony about 2000 kilometres off the south-east coast of the Indian subcontinent, his parents were Tamil-speakers who had migrated from Madras, probably in order to work as indentured labourers in Mauritius’s sugar plantation economy. But shortly after they arrived his father began working for a local magistrate as an interpreter, and later he caught the eye of the first Anglican bishop of Mauritius, under whose influence he converted from Islam to Christianity. He then worked for the Anglican Church — or more particularly the Church Missionary Society and its Christian Indian Association — as a catechist to his fellow countrymen and women.

Thomas Shadrach James, whose birth name was Shadrach Thomas Peersahib, acquired a good education at a private school in Port Louis, and became a Methodist before he migrated to Tasmania in c. 1878 after his mother had died and his father remarried shortly afterwards.

In early 1881 James met Daniel and Janet Matthews and approximately forty of the people from Maloga while they were Brighton Beach in Melbourne and decided to return to the mission with them. There, he became the assistant teacher in the mission’s school and soon performed nearly all its educational work.

From the outset, James was sympathetic towards the people at Maloga, probably because he identified personally with their experience of British colonisation. They in turn came to regard him as a kindred spirit and part of their kin community. The latter aspect of their relationship was cemented when he married Cooper’s sister Ada.

In time, James would play the roles of both advocate and mediator for the Aboriginal people at Maloga. He not only taught the children during the day but the men at night, taking what he called the scholars’ class in one of the men’s huts. He urged the people at Maloga to embrace the opportunities that Christianity and civilisation (as he saw it) had to offer and to assert their rights as British subjects.

James was to teach several children at Maloga and Cumeroogunga who later played a major role in the fight for Aboriginal rights: Doug Nicholls, Jack and George Patten, Bill and Eric Onus, and his own son Shadrach Livingstone James. Indeed, his work at Maloga and Cumeroogunga is one of the main reasons why a significant number of people from this mission and reserve played a major role in Aboriginal affairs across several generations in the twentieth century.

For more biographical information, see George E. Nelson, ‘James, Thomas Shadrach (1859–1946)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/james-thomas-shadrach-10610/text18855, published first in hardcopy 1996